This is the most difficult article I’ve had to write. At the start, I thought personal stories would be the most uncomfortable. There is pressure in attaching your ideas in the smallest way to towering thinkers like Zhuangzi, SuDongpo, or putting an unconventional viewpoint on The Daodejing out into the world. As it turns out, facing my unknowns and limitations is quite a confounding experience. Looking back at who we were is always challenging to the ego, even after we feel we’ve turned a corner. We fancy we’ve become a better version of ourselves.

This is one of those times. A story about a memorial to history, to loss, to family, to preservation, and to culture that is so macabrely, chaotically beautiful that you will be left dumbfounded asking, “What is this, and why am I here?”

I was here because this experience was specifically asked for by me, and publicly promised to all of you nine months before. You see, in March of 2024 we had made a trip to Jingdezhen, the centre of Chinese porcelain design and manufacture since 1000CE onwards. Among the museums and kiln sites is a quirky tourist attraction called the Porcelain Palace, the dream of Mr. YuErmei, a then-82-year old scion of local industry. Looking very like a colourful birthday cake set in the hills outside Jingdezhen, it is a weird experience being there. We had a good time appreciating the art and spectacle. You could read about it here.

Extra emphasis is necessary. The following story will mean more if you read this first.

While researching Ms. YuErmei’s story, she named “The Tianjin Porcelain House” as her inspiration for the project. She didn’t want Jingdezhen to be forgotten, or even to play second fiddle, to a monolith in Tianjin. She felt Jingdezhen, as the historical centre of production, had the right to make porcelain and ceramic monuments, and she aimed to make hers the best. I found that quaint and amusing, and determined then and there to seeing The China House in Tianjin, as it is officially known, and make my own comparison. With me as a judge, we would see who comes out on top.

The point of this long preamble is to caution you NOT to do this. There is no comparing The China House. Comparisons will lessen and trivialize the story. So before you see this for the first time, be prepared for your first reaction, and to dismiss it.

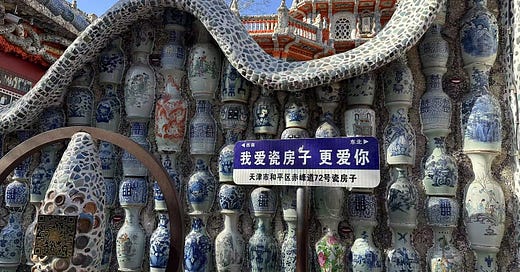

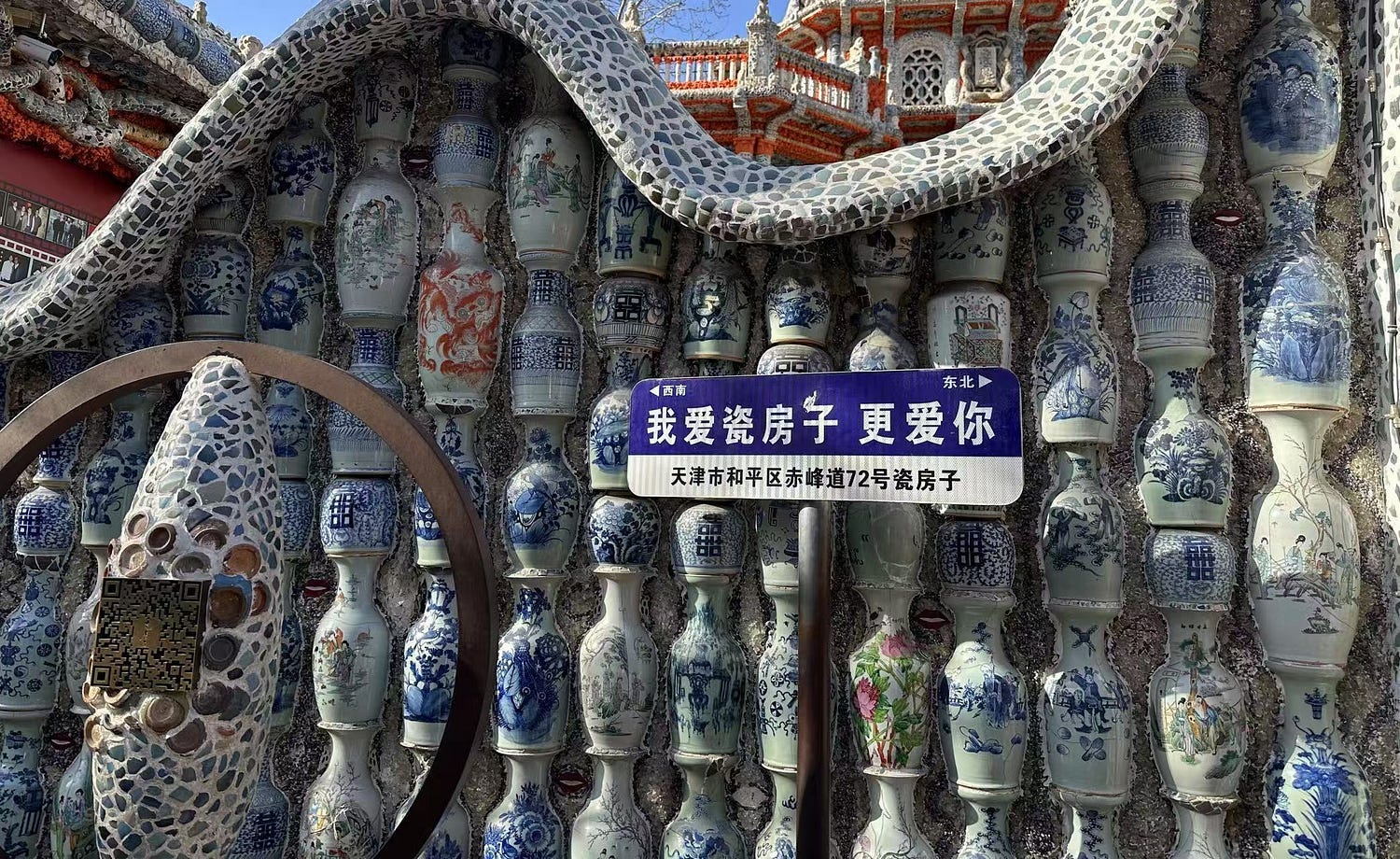

This is The China House of Tianjin. Down the road from the Starbucks-in-an-old-bank, The China House is built around a converted French style home in the old French concession. A home for governors and diplomats, the house itself is more than 100 years old. With a long history, and years of exposure and neglect, the building languished, until one Zhang Lianzhi purchased and remodelled it from 2000 to 2007 for 30 million yuan ($4.2 million). The building itself is the youngest feature of The China House. Everything that we see outside and inside dates from at least the Ming and Qing dynasties, anywhere from 500 to 1000 years old, or even more.

Do you have your first reaction?

I will share mine: “What a mess.”

I didn’t know what to think, and not thinking, the natural reaction is to laugh. Not at ourselves, as we should, laughing at our limited knowledge that makes a thing so incomprehensible to us, but laughing at the craziness and silliness of this person who might be slightly insane. While this might be the natural reaction, staying in that mindset would cause us to miss everything that matters.

My time in the business world taught me something that I have found applies generally: people always do things for a reason. People do not just do stupid things. When we see someone making a nonsensical decision, there is a problem. But the problem is not with them, it is with us. There are good reasons behind everything people do, and just because we may not be aware of what those reasons are, the reasons remain to be uncovered. These are the questions of culture; to see the curtain, wonder what lies behind, and make the moves that give us a chance to understand.

In person, the effect is an immediate overwhelming of the senses. Even the gated front wall exposed to the street is made from porcelain vases hundreds of years old. You get the sense there is symbolism in every piece, in the positioning, and in the relation to other pieces. I had wandered halfway through the house before it dawned on me that this was something more than I could understand or appreciate.

It takes more than an intimate, expert-level understanding of Chinese culture, religions, and history, to grasp the meaning and import of these messages. One must also understand the thoughts, values, and inspirations of the man who guided the design and made every decision, Mr. Zhang Lianzhi. The China House really is the PhD exam for aspiring students of Chinese culture and history. I was not surprised to read that even locals can have a dismissive attitude, with local tour guides snapping a quick pic at the entrance before shuffling their groups onward. We witnessed this ourselves out on the street. An intimidating prospect to try and explain coherently, so no wonder many choose instead to push past.

So this story doesn’t slip out of our grasp and become an incomprehensible book, I will hold myself to describing a selection of the details we encountered. I’ve already decided to return for another crack, the next time better armed by studying for the exam in advance.

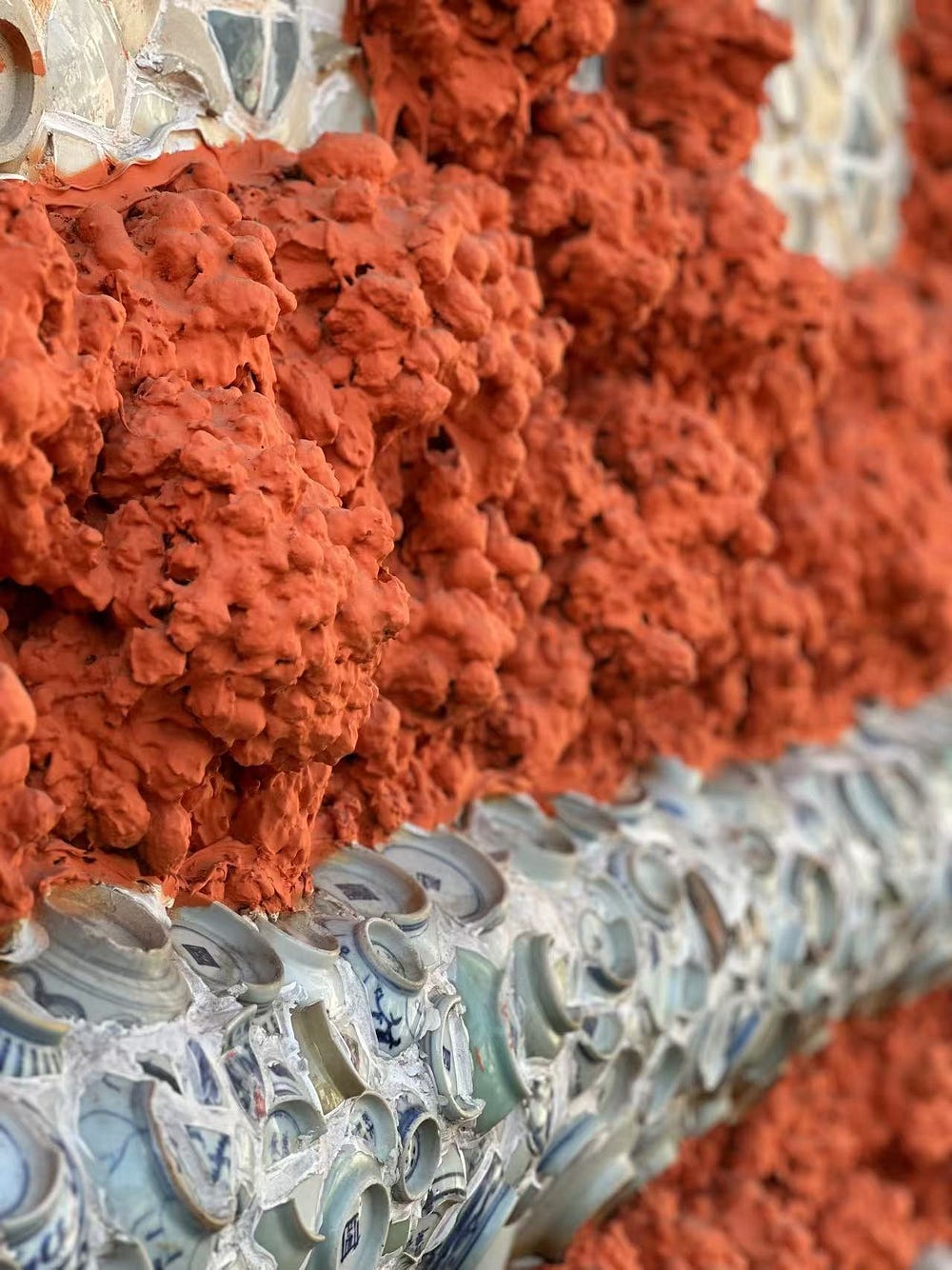

The colour scheme is among the first things to stand out. Mainly bluish fields of ceramics framed by heavily textured orange stucco that almost gives the impression of bubbling within the walls. Inside, the walls keep the orange colour but transition to blue on the upper floors. A subtle change that one only notices after its happened, as if we’ve ascended into the clouds.

There is an otherworldly look about the exterior. Is this a building or a living creature? Perhaps a building taken over by something alive, but camouflaged. When does the building end, and the creature begin? Twisting columns wrap around, looping on themselves in an instinctive, languid way, writhing to the top to form the word “China”. The imagination makes the shards and plates into scales, an alien dream only the subconscious could inspire. Mr. Zhang has brought the dream into the world.

There are hundreds of pieces embedded in the exterior. Some are placed for good fortune but I couldn’t begin to know the origin and meaning of each. Mr. Zhang travelled and personally brought back many of these pieces from the then-owners in Brazil, Canada, Australia, France, and Hong Kong, among others. He would have had to negotiate and purchase each piece, then arrange safe transportation and storage before installation in the façade. I cannot imagine the expense.

European porcelain also makes an appearance, such as examples from Meissen, as a kind of general celebration of the art and craft of porcelain making. Any of these antiques are at least 100 years old.

As we mount the stairs to the entrance, impossible decisions dangle in the periphery, teasing our attention…on the right, suspended by a crude wire is a deep cerulean burgundy plate or serving bowl. Why is it there? The sign does nothing to dispel the mystery, only deepening the sense of disorientation. The yellowing sign states that this plate is from the Song Dynasty, a period from 960 to 1279. This plate is at minimum 746 years old. By any rule of normalcy it would be under glass in a museum or locked away by a collector. Am I a bit mad that I want to reach up and touch it?

As I dismiss the urge to cause an international incident, a lion smirks widely at me from the doorway. A brightly coloured Ming Dynasty lion, the female half of a pair. Her male counterpart has been lost to conflict or neglect, leaving her mate as the largest preserved lion of this type from the Ming Dynasty, 400 years old. Meant to quell and intimidate evil, you can touch her head for luck.

The China House is a museum, but not like any official museum we are used to seeing. Official museums of collected treasures and artworks reside in prestigious, often modern, buildings. They represent and promote the character the country wishes the world to know, often including the message, “See our greatness.” I love a good museum, for what we can learn of the culture it represents, and the value of the art it protects.

The China House is a private museum. A private collection ordered in an intensely personal way. And like being invited to someone’s home, seeing their hobby that has consumed much of their time and interest, the meaning and import will always lie most intensely with the owner and author. It is not that he doesn’t wish to explain what it means to him, but how could he, other than by showing us?

The French designed a three story structure, plus an underground level, with balconies on the second floor. A staircase spirals around the perimeter, spinning around a central shaft that pierces each floor. The baluster looks the original French design, the handrail encrusted with ceramic fragments. Characters and sayings made with inlaid ceramic rest in the bubbled walls. Dragons, roosters, tigers, and heroic figures cover the surfaces, many of these signed by well-known artists.

The bones of the structure are exposed, each floor open-plan, the structural pillars stuccoed orange, the ceiling and piping visible, a nakedness that belies an impression of totality and calculated design. Do you ever look into the corners of your dreams? Up to the ceiling? We move through our dreams on waves of emotion, trifling details fading even as the images pass by our consciousness. Totality is not the point.

And there is furniture. Oh, so much furniture: wardrobes, tables, drawer and doored-chests, settees, altars, all kinds of salvaged antiques. They line and stack the walls, soldiered two and three deep, without rhyme or reason. My eye fixes on details, a knob, an inset door, the way a leg angles away from a top. I spent 22 years absorbed in the global furniture business, borrowing inspiration from pieces like these, and I’m feeling a bit triggered. A warehouse for his collection and not enough space to share it, today these will only be background for us.

But naturally, you must be wondering, just who is this Zhang Lianzhi? The China House is a singular and tightly focused vision. It is his vision, and I do not see any tell-tale signs of design-by-committee, or “democratization” of decisions. It was reported that the contents of the museum are worth 2 billion yuan ($280 million). What sort of international man of mystery would be driven to invest a substantial chunk of his life in such a project?

I found gathering information about Zhang Lianzhi himself rather difficult. Fragments are all there is. A story here, a quote there, an anecdote, that is all. He doesn’t give interviews, and his current whereabouts and activities? I came up empty-handed. So what do we know? He was 53 in 2010 when he said that he renovated the old French house to hold his collection of Chinaware and furniture. He lived in Canada for a time, probably having emigrated. He made his fortune in restaurants, maybe the seafood business, possibly selling cloth. His family probably has a long history of aristocracy, familiarity with expensive artwork and fine living.

He has a vast personal knowledge and emotional connection to Chinese antiques, likely inspired and driven by his close relationship with his mother. In one story, he recounts a teenage memory in which his mother was distressed by a broken chinaware inherited from ancestors. He used the pieces to build a pyramid. “You cannot imagine how happy she was when she saw it, ” he said. Such moments stay with us for a lifetime.

I surmise that much of the travelling and searching out of these antiquities was done himself, but certainly not alone. He clearly has close connections to officialdom and approval to accomplish the collecting of all these treasures and freedom to display them in such a unique way in this particular location.

Completing the circumference of the second floor, we go outside to an octagonal balcony overlooking the courtyard and offering a closer view of the many antiques that decorate the exterior. Now look up to the ceiling, covered in serving plates.

One hundred fine porcelain dishes from the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), many with fish and lion motifs, are arranged tightly around a singular pink plate in the centre. This is the 270 year old plate from the Qianlong era of the Qing Dynasty, used by the royal family. It has survived to reach this resting place, though not without scars.

This plate is an example of “ornamental” porcelain, as opposed to “practical”. Pieces of superior craftsmanship were selected by the Emperor to be used as display, and this plate was one of those selected. Notice the mix of images painted on the surface; there are furniture, drums, potted flowers, and “sacrificial objects.” I find it quirky and chaotic, perhaps not my choice for high honour, but a reminder of the gulf of culture we peer across.

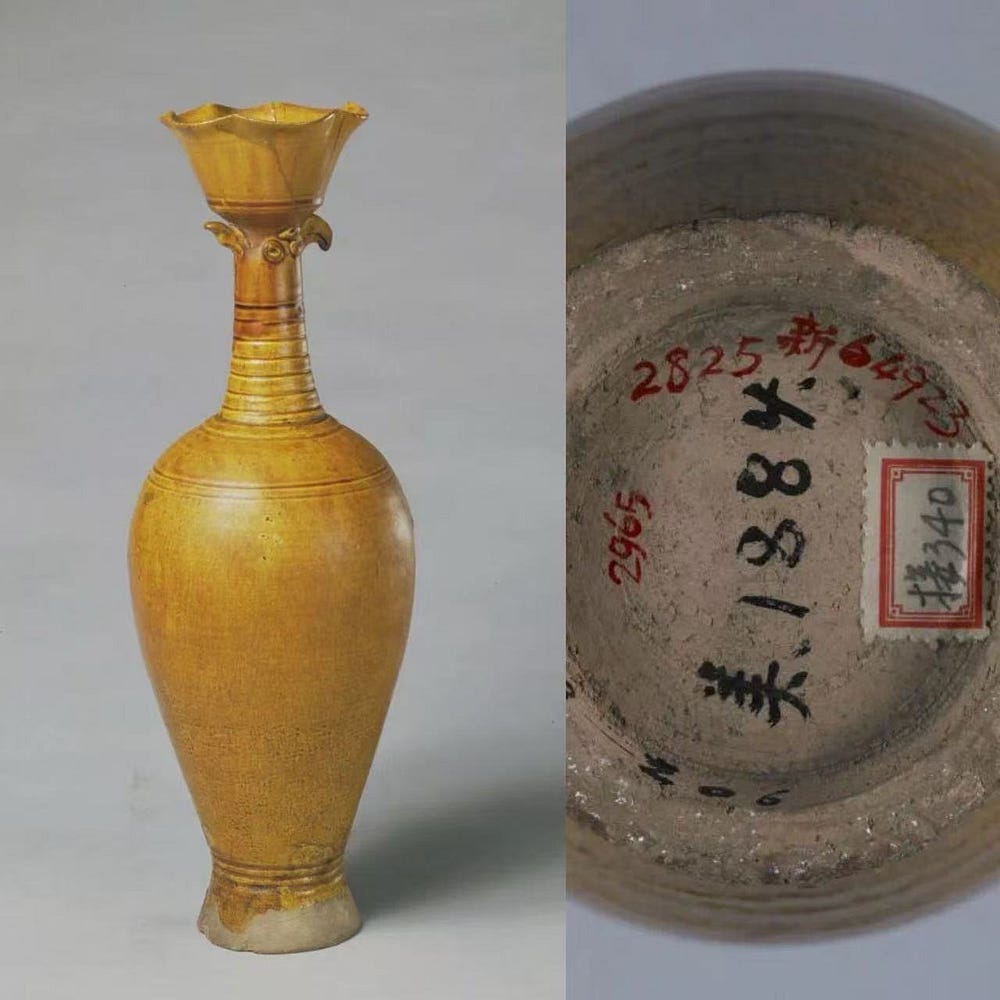

Looking over the balcony, off to the right, another incredible decision dares to defy logic. An elegant golden bottle with a flowered mouth is standing under glass at the top of a metal pole in the alleyway next to the house. There is no fence, no signpost. It is as if the design aesthetic of the house spilled outside the wall, or perhaps a rendering error in the Matrix placed this outside the boundary.

This is a “yellow glazed phoenix head vase”. The shape and colour may be a familiar Chinese design, but this example is one of the first to have the yellow glazing. Only the aristocracy had access to and eligibility to use these vases, for wine vessels and whatnot. This sample standing all solitary at the top of the pole is from the Tang Dynasty. It is 1300 years old and the oldest existing complete piece in the world.

Now let’s return to the thick tendrils that wend and wrap their way around the house, to where they culminate, on the ceiling of the topmost floor. Centred above the central maw that runs down to below ground, the limbs reach a crescendo here and terminate spectacularly in a meeting of six heads, the faces silently regarding each other. The effect is mystifying and stays with you.

According to the tour guide we listened in on, and without whom we would have few facts about The China House, this is a six-headed representation of the Chinese mythical characters Fuxi and Nüwa. These two are brother-sister, also married or not depending on the story, and often depicted as having snakes bodies with human heads. Together, they created humanity.

These are divine beings, creation deities, central to Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. This is my introduction to these myths and characters, and the insight is fascinating. The weaving of these deities and references into the house is so unique and individual. I very much doubt a similar interpretation can be found anywhere. This is how Fuxi and Nüwa can be depicted:

Walking about the house, knowing little and understanding less, my mind conjures its own connections. The attachment between people and snakes, it must run deep, far predating civilization. We do love our stories. Look up Robert E. Howard’s Conan story, “The God in the Bowl”. The physical description of his creature is uncanny. Did Robert E. Howard read Chinese mythology? Or consider H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Shadow Out Of Time.” Imagining sentient beings with lizard characteristics for good or ill has a long history. Adam and Eve is too obvious. The rivalry and interwoven nature of the connections between snakes and humanity is forever embedded in our instincts.

So why do they each have three heads? That is a China House unique perspective, inspired by The Daodejing, chapter 42, which says,

“The Dao produces one. One produces two. Two produces three. Three produces all things and creatures.”

This is the origin of us, the myriad creatures, and there is more. Taken together, the six heads reference The Universe, through the six directions: North, South, East, West, Up, and Down. This artwork attempts nothing less than the expression of the root of Chinese culture, and all of it centred around the Yin Yang symbol, showing the Daoist spirit, or harmony between Heaven and Humanity. Quite the ambition, to physically represent the root and passion of Chinese culture.

At the bottom floor, a sort of “well”, to catch the good fortune and wealth that Heaven makes available. A 400-year-old Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) chalice urn that was used for catching water, signifying wealth. The eight “arms” radiating from the pot also refer to flowing wealth. Peony and bamboo designs circle the exterior. The peony is the King of flowers, a symbol of riches and prosperity. Bamboo, by being tall and straight, signifies longevity. Everything in The China House means something.

Finally at the last, we will cast our attention to one of the smallest details of The China House, the trivial petals of a flower.

This wall mural is seen early, positioned on a lower floor, where we had just begun to recognize the value and necessity of the tour, and the indispensable guide. As we shadowed the group and listened in, she was explaining the surprising origin and value of the raw materials used by the artist.

Look closer at the two red flowers, made of a rich and deep burgundy coloured porcelain. These red pieces are the famous “Jun porcelain”. Creating the pure red colour is incredibly difficult because of both the finely tuned kiln technology, the temperature control, and the precision of the chemical handling. There are many examples of middling results that illustrate the challenge, and comparisons with the famous blue-white porcelain designs shows the limitations. The ability to make a deep red colour free of cracks peaked in the 1400s. Now understand this — the techniques used to make these have been lost and not rediscovered. This colour cannot be replicated even today.

Where did all these Jun pieces, and for that matter the other 400 million fragments, where did they come from? That is a story. For much of it’s history, Tianjin has been an important transit port for goods moving into Beijing. Ceramics and porcelain would be shipped on the waterways. Naturally, some of the shipment would be damaged in transit. The common practice to avoid punishment for damage goods was, you guessed it, throw the broken pieces overboard. By the time the Qing Dynasty was ending, the waterway was becoming clogged by this debris, by the fragments and much else. Zhang Lianzhi’s ancestors, the prior three generations, were among the families that dredged and rescued these fragments. They felt the value of what had been discarded as trash.

So now I finally see. The China House is not about porcelain. Porcelain is the only language enough a part of Zhang Lianzhi’s life to carry the message. Broken things still have value. Value in and of themselves, because of what they are and what they represent. Despite what broke them, they can still go on to be useful in new ways.

These little red pieces of a previous life that can never be put back together. Going back to erase the past is impossible. We don’t even know how to recreate what was. But now repurposed, carrying the history forward to remind us what happened, they are in a way more than before. New meaning. New purpose.

For any of us that have felt broken, this is something to remember.

We are here because I asked for it. My reasons were merely curious and shallow, but does how we reach a place matter? Perhaps not, if we stay curious and are open to a deeper encounter.

From this place of acceptance, I can understand and even find a use for this revealing Lonely Planet blurb about The China House on their website:

Tianjin’s tackiest sight by a long shot, China House is porcelain collector Zhang Lianzhi’s ode to both porcelain and questionable taste. Vases and mosaic-like shards are embedded in every conceivable vertical surface here, making for a truly bizarre façade. Snap your requisite selfie from the outside and move on — the interior is essentially more of the same.

And this is what brings me to places like The China House, and people like Buddhist Master Hongyi, SuDongpo, and yes, also The Daodejing — layers of mystery and what they can reveal. Not only what is revealed about the subject, but about the many viewers and crafters of their stories. If we only look for what we expect, then that is all we will ever see. And if you believe that reveals something central to me, then you would be right.

To be honest it is absolutely mesmerising. Boggles my mind the value of the items within. Reminds me of Dali and Gaudi…. A bit of the surreal?

Somehow this China House seems perfectly situated in Tianjin. In Shanghai it would be just another expensive folly. In Tianjin it's a statement of purpose. How did you feel seeing all that antique furniture surrounded by so much... so much "orange'!!? And that Tang dynasty, one of a kind, irreplaceable, 1300 year old vase standing happily outside - another 'perfect in Tianjin" placement. Everybody can see it here. 20 tonnes of brazilian agate? Qing dynasty plates on a ceiling? A Song dynasty plate you can touch? Like I said, this collection is perfect for Tianjin. I don't even know what to think!