Profound art that lasts, great statesmen, mavericks who go against the grain of their own times, they are all men and women, very like you and me. We all have stories. Their stories are parsed and studied for significance by those looking for answers and meaning. Thus, their stories are filtered through the perceptions and purposes of the storytellers, becoming part of the narrative. Stories and their many tellers, shining light and shading the truth.

Master Hongyi might be one of us born with the gift — or the curse — of having to be his own man, of bending the probability of his existence to his own design. This might be your first introduction to Master Hongyi, or he might be an admired teacher and inspiration. Either way, I feel the weight and responsibility of attempting to introduce his story.

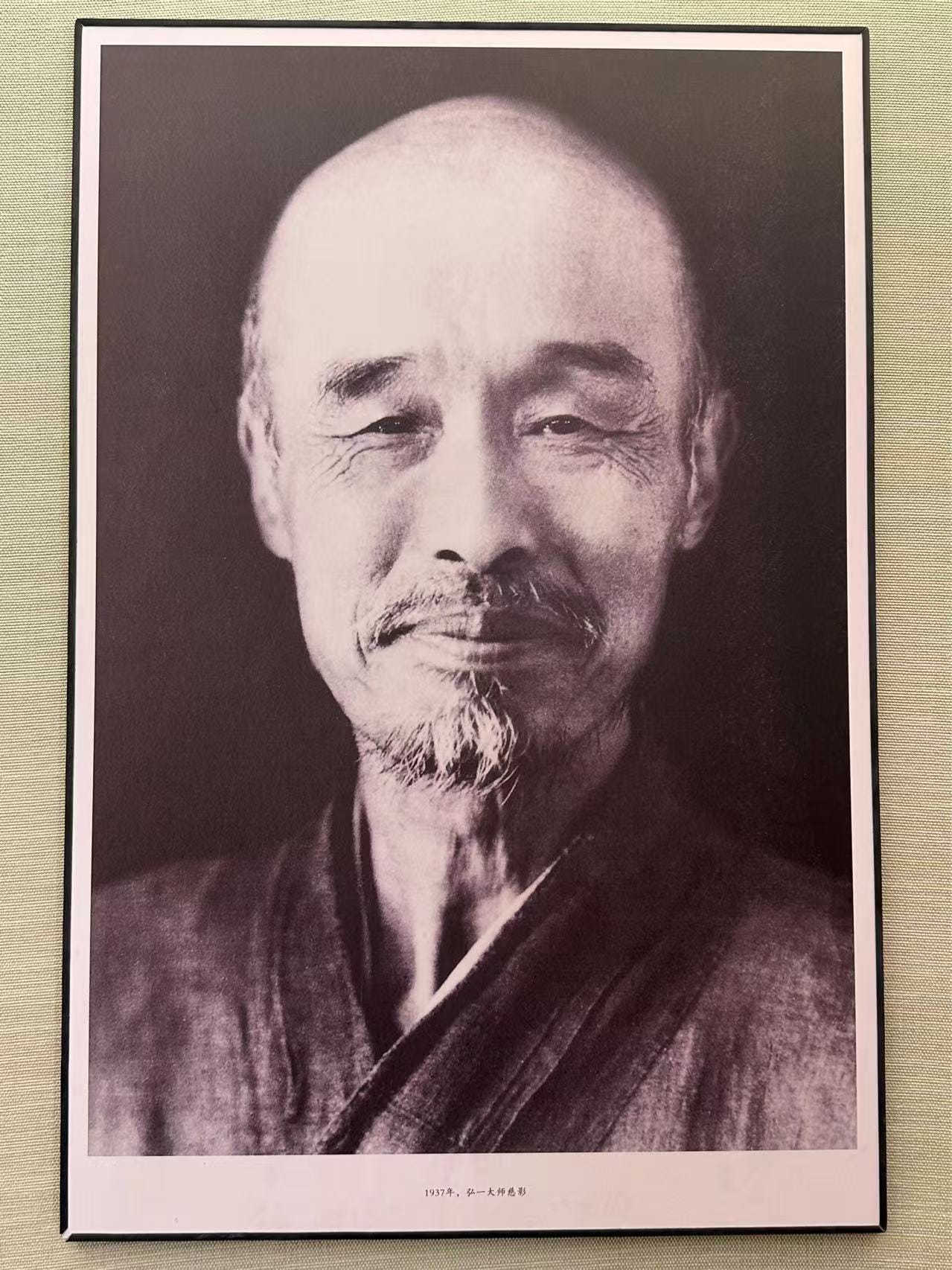

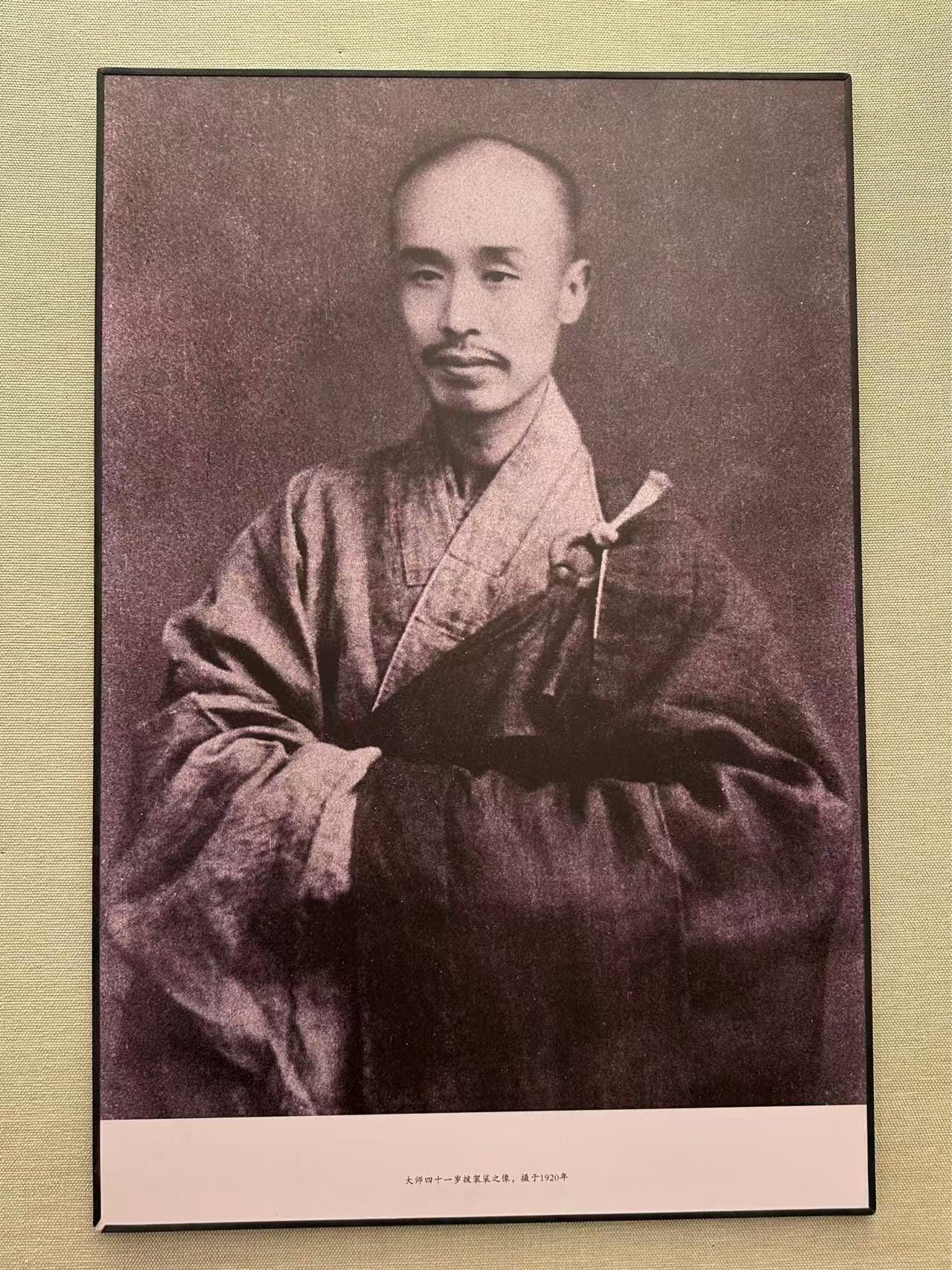

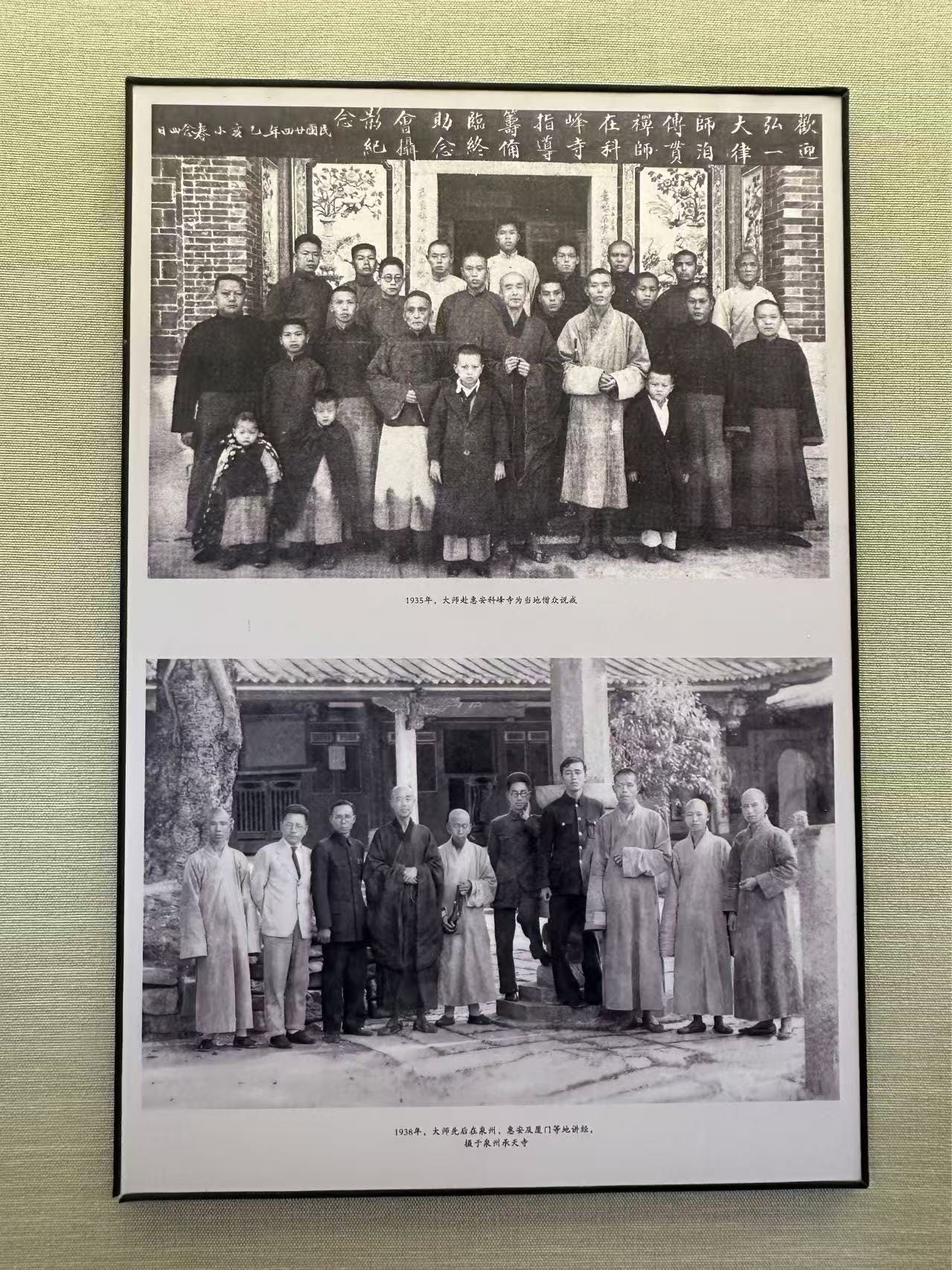

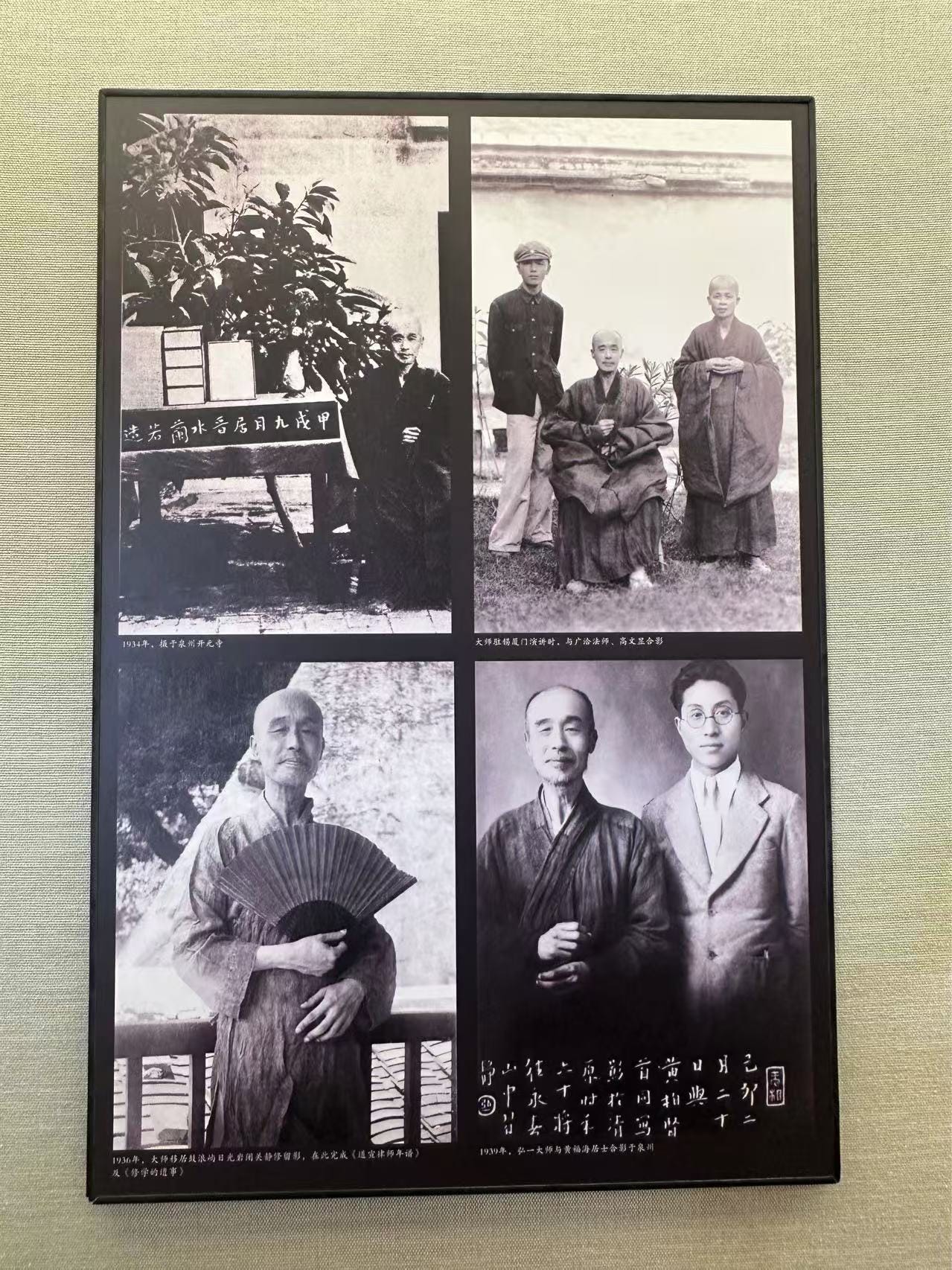

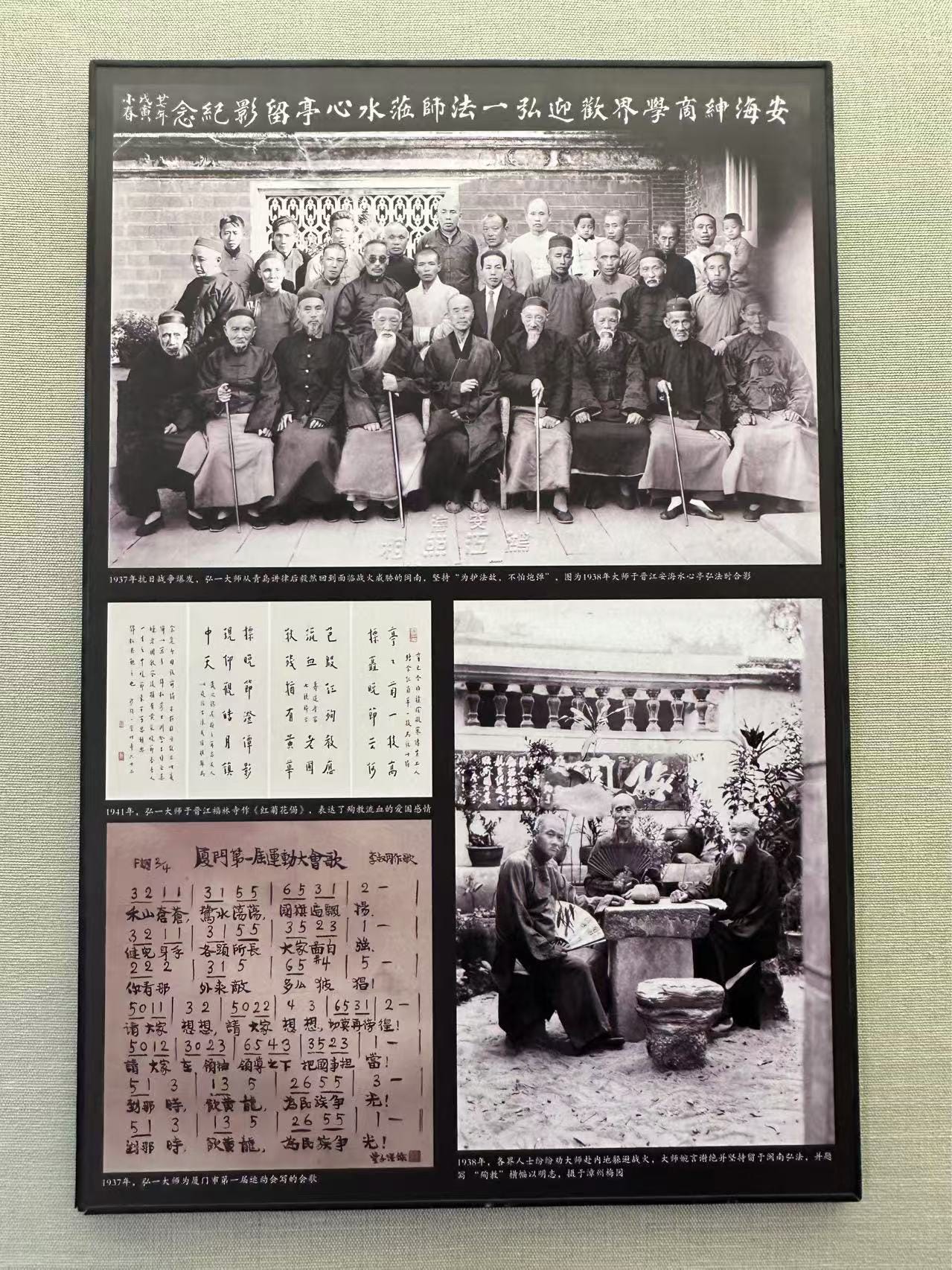

We start our narrative at the end of his story, in Quanzhou, where this eminent Buddhist scholar passed away in 1942. Kaiyuan Monastery showcases a memorial hall that includes photographs of Master Hongyi at different stages of his life, samples of his calligraphy, paintings, and sheet music that he composed. This simple space provides us the opportunity to make an overview of his life, and a good beginning.

The gallery is shine and modernity within the confines of 1000-year-old Kaiyuan. I couldn’t felt thinking of a Bond villain going through one old door onto a studio set made up to look like a snazzy lair. Beginning on the far left, by going around the three sides of this room you will get the focal points of Master Hongyi’s life, and a few choice clues to the whys.

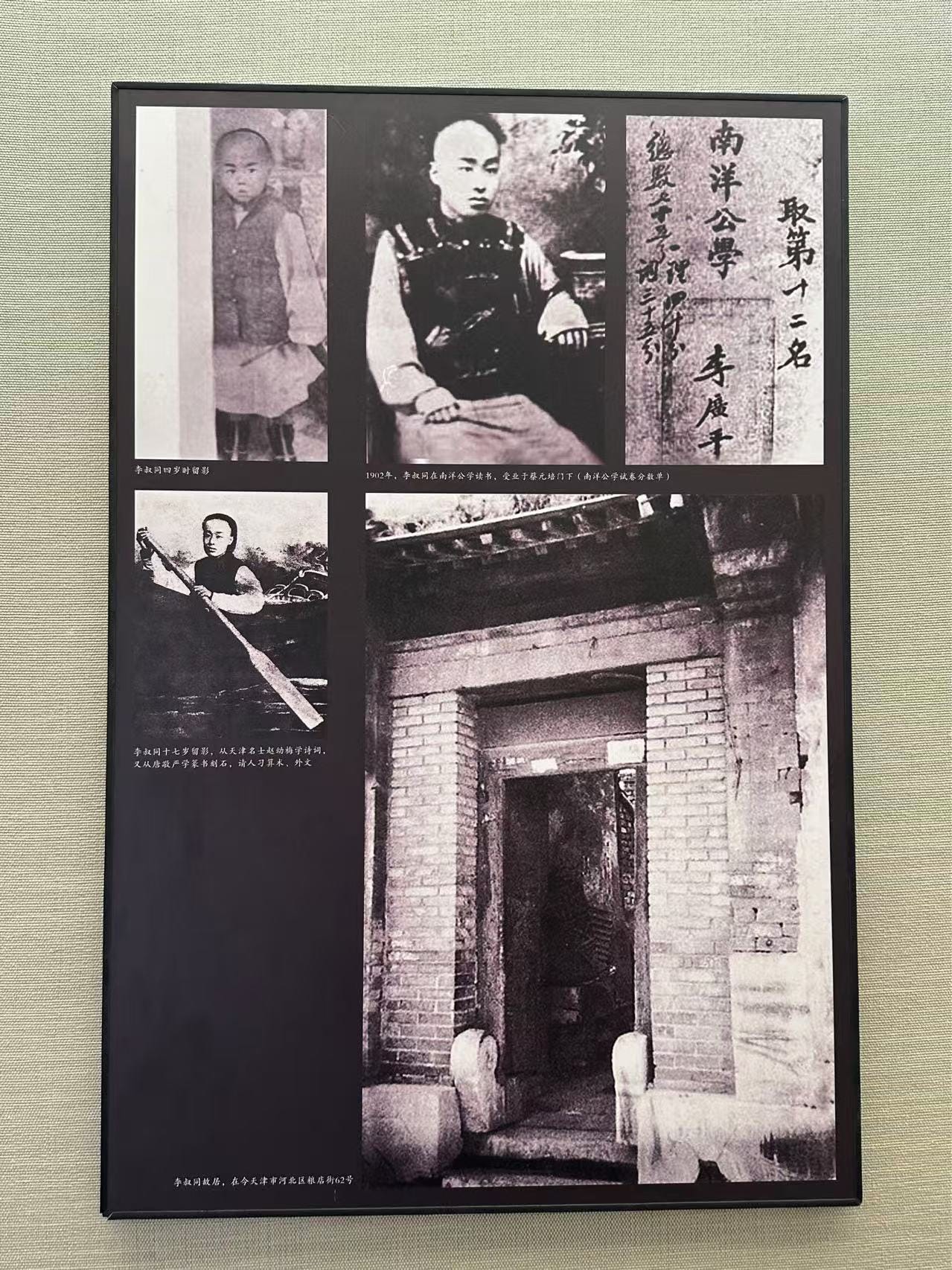

Buddhist Master HongYi was born LiShutong, in 1880, to the scion of a rich banking family. Much of his youth was spent in the northern coastal city of Tianjin. A quick aside, Tianjin is one of my favorite cities. The unique atmosphere and rich culture; the food, my goodness, and I met my wife there. Anyway, Li ‘s father was 68 years old when he was born, and his mother, I believe, was 20. Moreover, Li’s mother was not the first wife of his father, but the fourth. This was common practice at the time, particularly for the very wealthy, but it meant that Li had a number of older brothers and a large family of competing interests and intrigues.

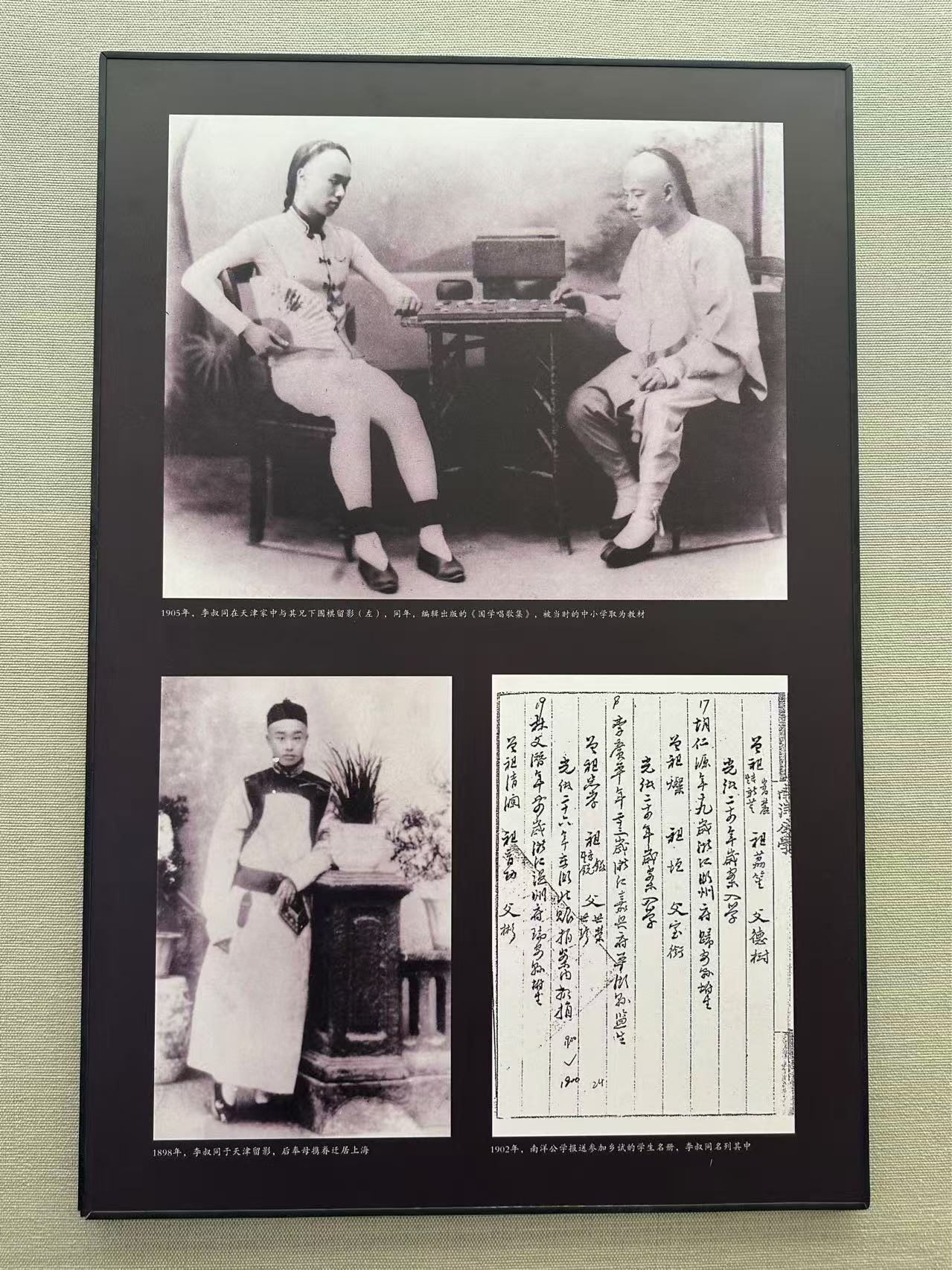

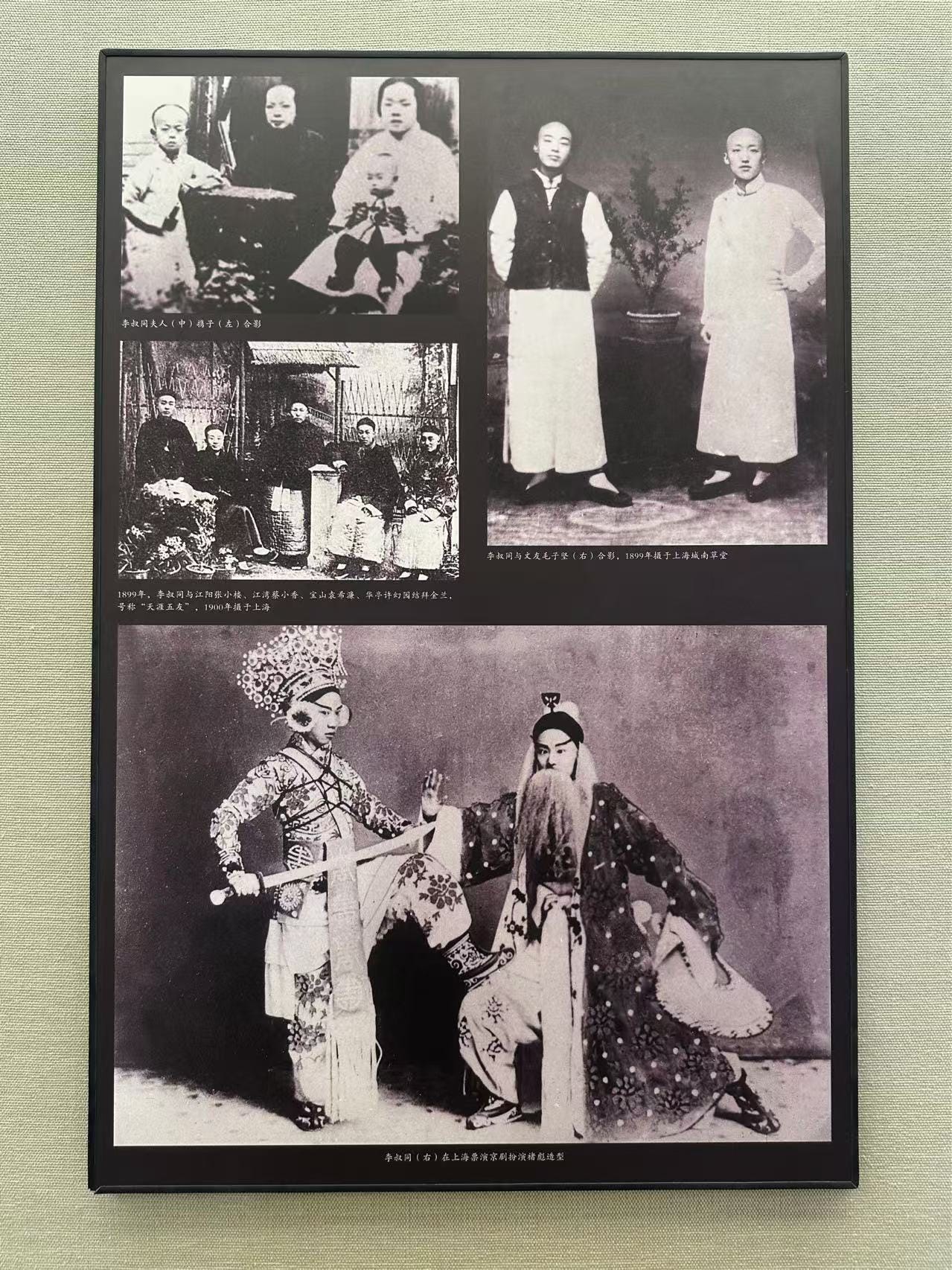

Above left, is Li’s former residence at №62 Lingduan Street, and we see Li at four years old, aged 17 with the paddle, and sitting at 22. Although this gallery doesn’t mention her, and she is only pictured once later, Li was married at age 16 to a girl selected for him. Again common practice, but I’ve read that this never became a love marriage, though she was mother to three of Li’s children. I can’t help but notice that Li never smiles in these pictures. Perhaps this is also a sign of the times.

In the late 1800s, education was an expensive and private affair. Li learned poetry from Zhao Youmei and seal script and stone carving from Tang Jingyan. He moved between Tianjin and Shanghai, his mother’s home city, as he furthered his education. Above right, Li (left) plays chess with one of his older brothers in Tianjin.

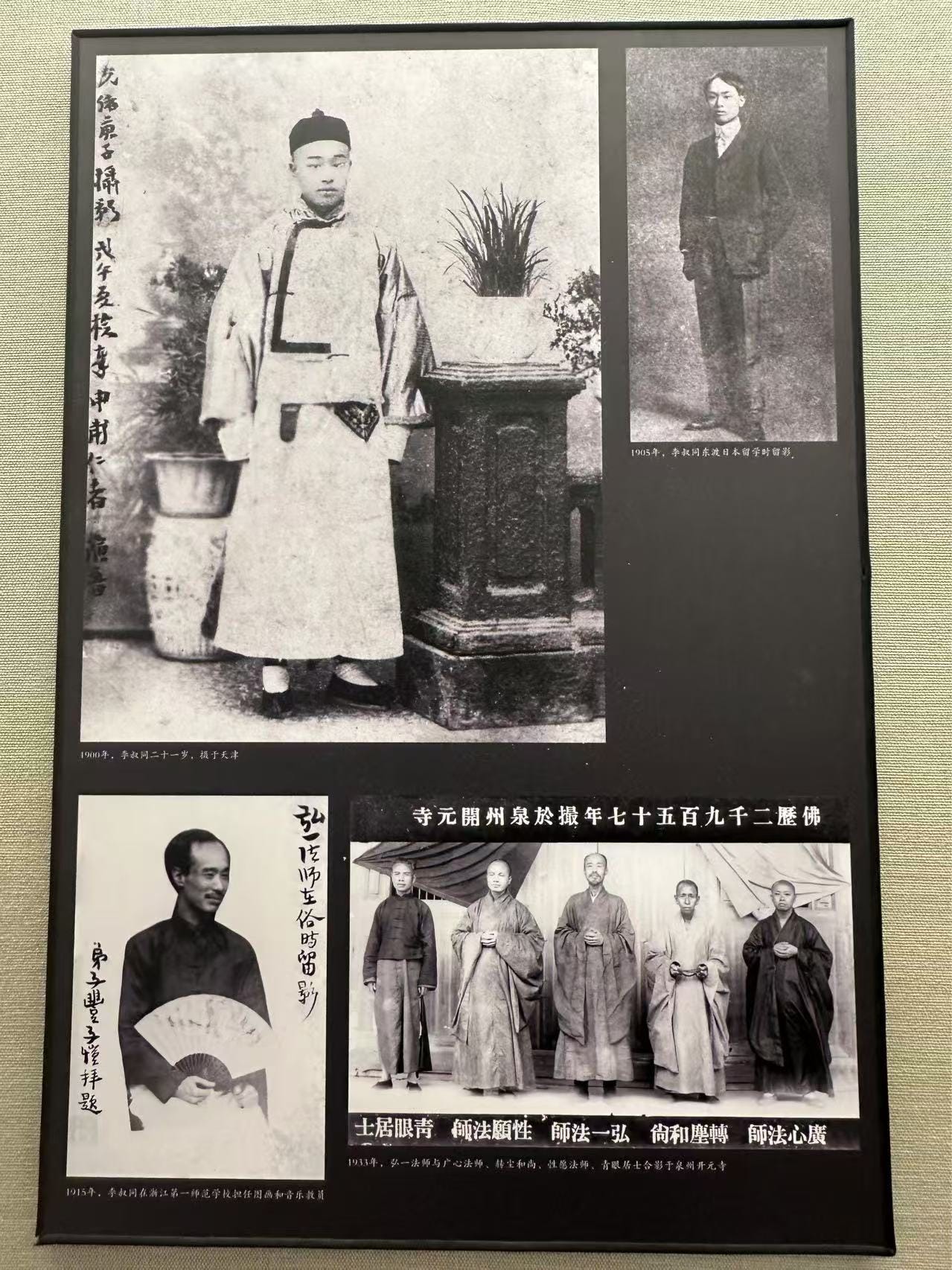

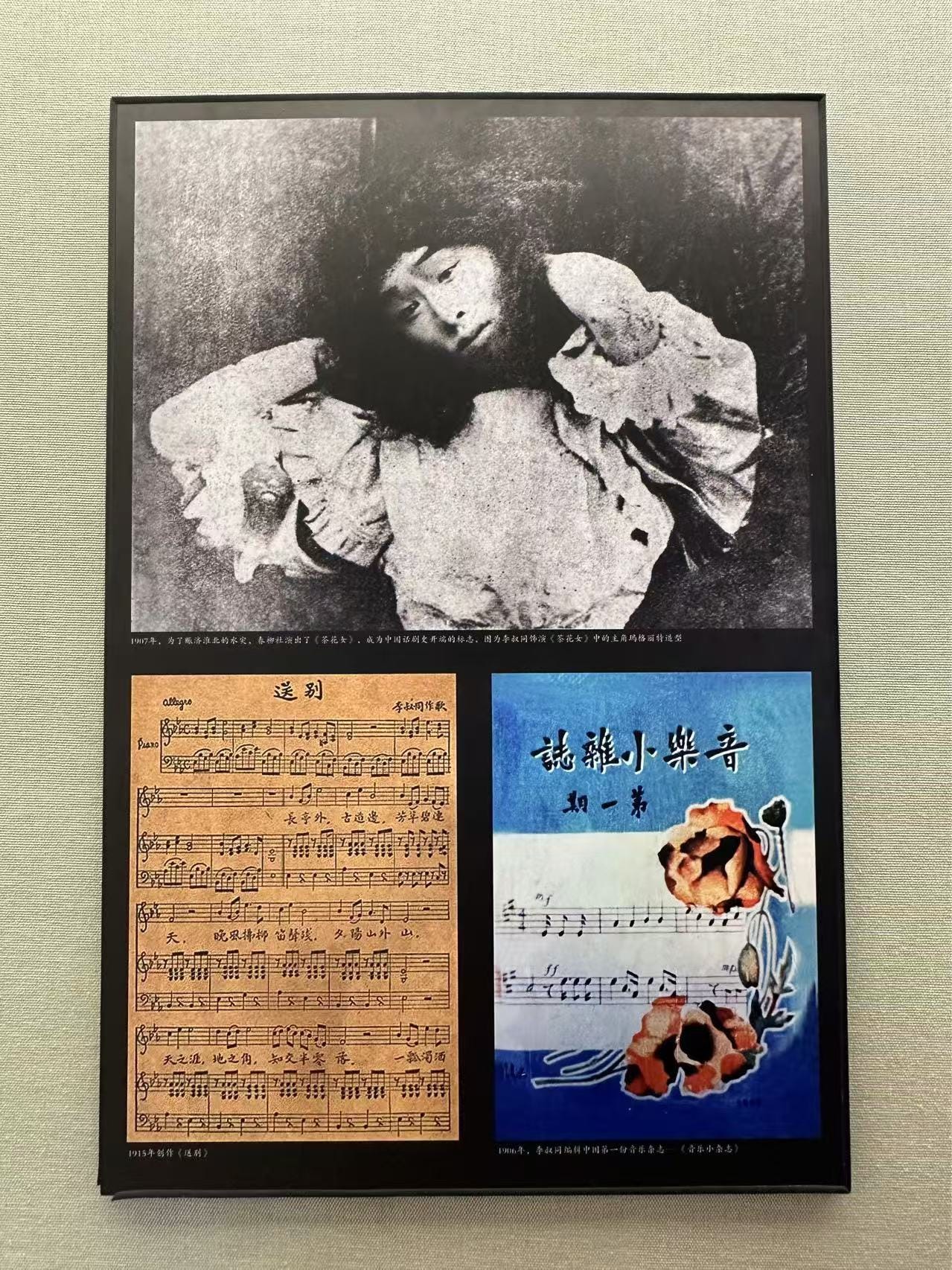

Li’s education and artistic prowess took him to Japan, another rarity in those days. Here he is, looking sharp and refined at 25 years old, studying in Japan. His performance and music composing flourished during this time. In 1907, center top, Li played the lead protagonist, Marguerite, in “La Dame aux Camelias”. The famed Alexandre Dumas wrote this play in 1848, to be later performed by the great Sarah Bernhardt in 1896. Long Time Reader, you will recognize Sarah and this artist Alphonse Mucha who created her iconic posters in Paris…

Li met, fell in love with, and married his second wife in Japan. His Japanese wife is not pictured or mentioned once in this gallery, though she must have figured significantly in his life story. This was a mutual love marriage, though I do not know how they met, what Li’s first wife knew and when, or how they managed this arrangement for close to ten years. I do know that Li’s first wife remained in Tianjin, his Japanese wife in Shanghai, while he worked and taught in Hangzhou. They had two children together.

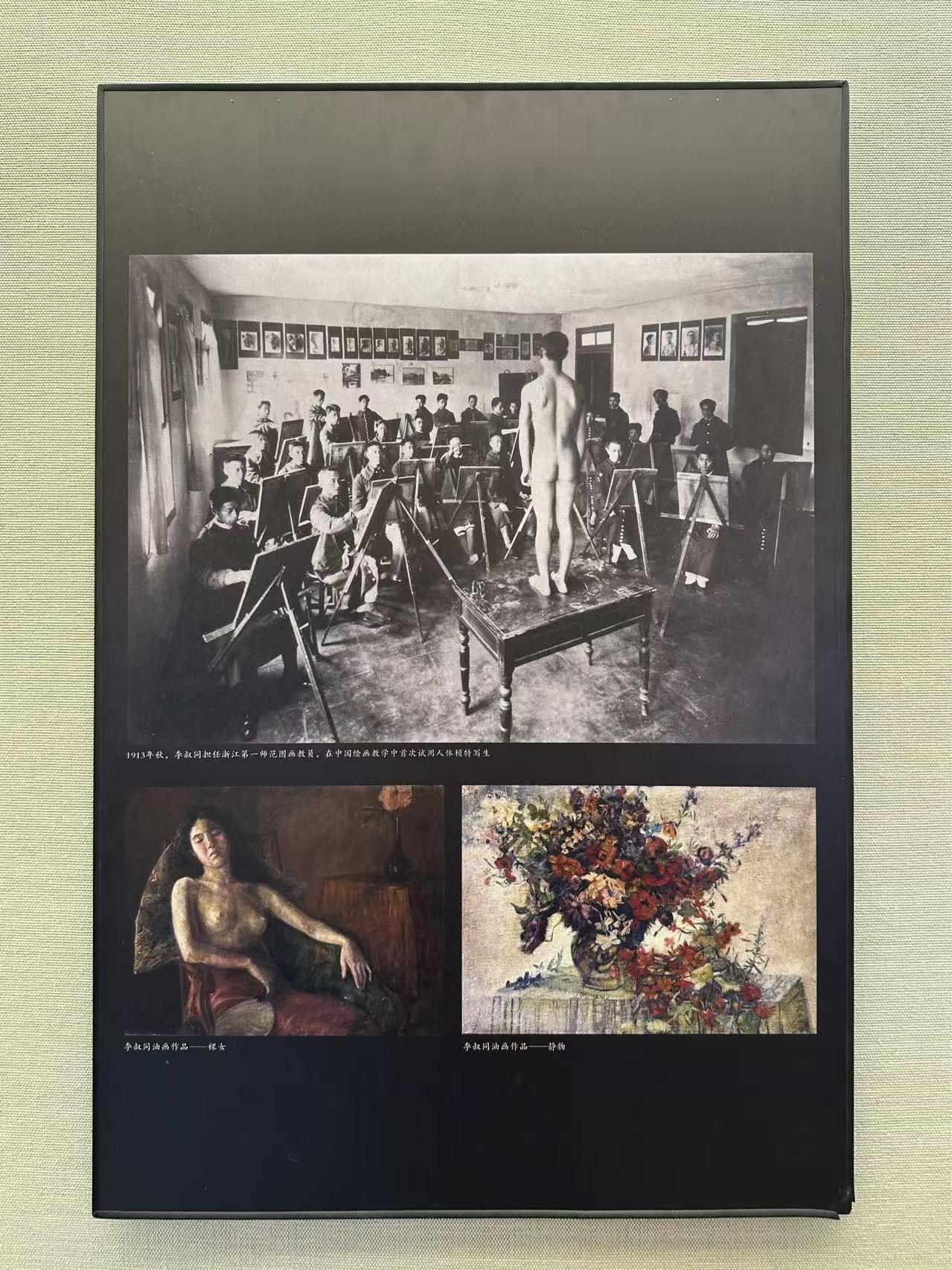

In Hangzhou, Li taught drawing, painting, and music composition. He was the first to paint and use nude models in his classes (below left). These were more conservative times. Seal carving was the art of crafting markers of personal identification on documents, like a signature today. Li and others have elevated this practical tool to an art form. Among his musical efforts is “The Farewell Song”, which I bet many of you will recognize, particularly those of us who live in Asia. Give the video a listen, let me know.

Now in his thirties, LiShutong was a well known artist, he was teaching, and his works were already considered valuable. But existence then took one of those odd turns that in isolation seem so rare and random, and yet all our plans and forecasts are but dust to be swept aside by Nature.

Something happened that changed the course of his life. I say something because what took place isn’t known to me. Maybe it wasn’t just one thing, but a lifetime of imbalance and hidden misery. Perhaps enough was enough, and a dam that had been holding for a long time just gave way. Maybe I’m looking for significance that isn’t there. But anyway, here is how LiShutong became Master HongYi.

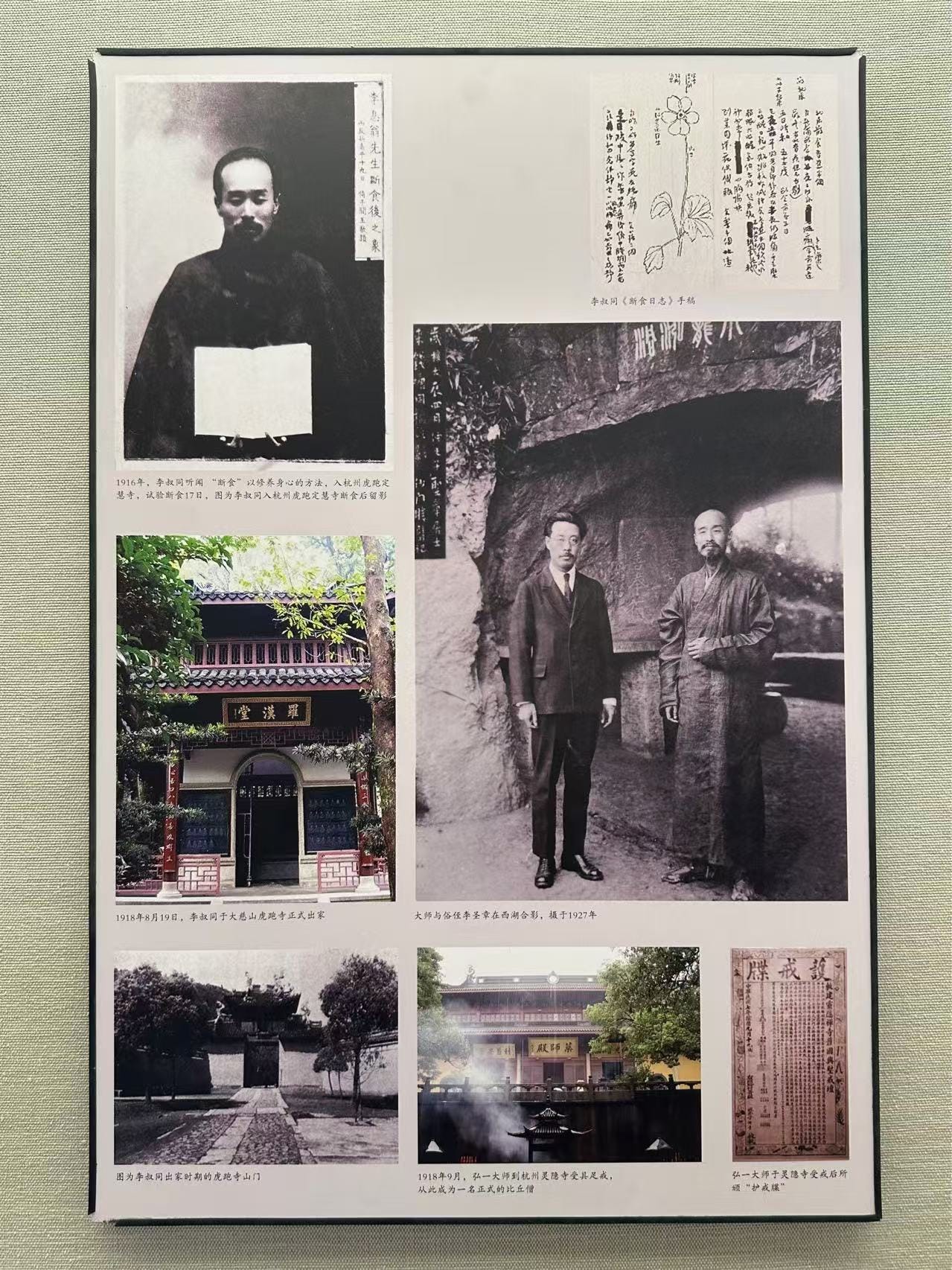

Li had been struggling with poor sleep and general health for some time and was looking for a solution. A colleague and friend had come across a Japanese article about the benefits of fasting, to “renew the body and the mind”. Li decided to give it a try, but he couldn’t do anything without full devotion. So he went looking for the best place to fast in meditation, and found the Hangzhou Hupao Temple. He went inside, committed himself, and fasted for 17 days. He kept a Fasting Diary where he meticulously recorded what he consumed and how he felt. The experience transformed his outlook on life.

On August 19th, 1918, LiShutong officially became a monk of Hupao Temple where he took the Buddhist name Hongyi. In the same year, he received ordination in Lingyin Temple. From then on, LiShutong became Master Hongyi. He dedicated what remained of his life to preaching Buddhism, writing and improving the notes and precepts of his school. He followed the most strict precepts of monastic life without exception.

He gave over all his possessions to societies and organizations that would know how to handle his artworks, such as collection of seals, given to the XiLing Seal Society. He ceased painting, drawing, composing, the art that had occupied him before, and concentrated on writing scripture and giving lectures on Buddhist theory and philosophy. He freed himself from ownership of everything, to smooth his way to becoming a monk.

What his families thought of this, I have a longing to know. His five children, three with his first wife in Tianjin, two with his second in Japan, I think would want to understand why. What did they say to him, and he to them? Were they taken care of, did they continue to have any contact? There is no mention in this gallery of the fate of his families, either what happened to them afterwards or their opinions.

Withholding judgment in favor of acceptance is part of my practice, but finding this difficult, perhaps falling back on the narrow scope of the storyteller will give us the patience to keep on and reach deeper understanding.

In 1937, as the war with Japan got serious, Master HongYi remained in vulnerable areas, refusing to relocate. He continued to give lectures and composed the patriotic song “Red Chrysanthemum Verse”, in 1941.

Master HongYi entered the Wenling Nursing Home on October 2, 1942. He fasted, drinking only water, and on the 7th, willed the remainder of his possessions to a close associate. On the 10th, he wrote “Sadness and Joy Mixed” to describe his feelings on leaving the world. He then quietly chanted the Buddhas name and passed away peacefully on October 13, 1942. He was 63.

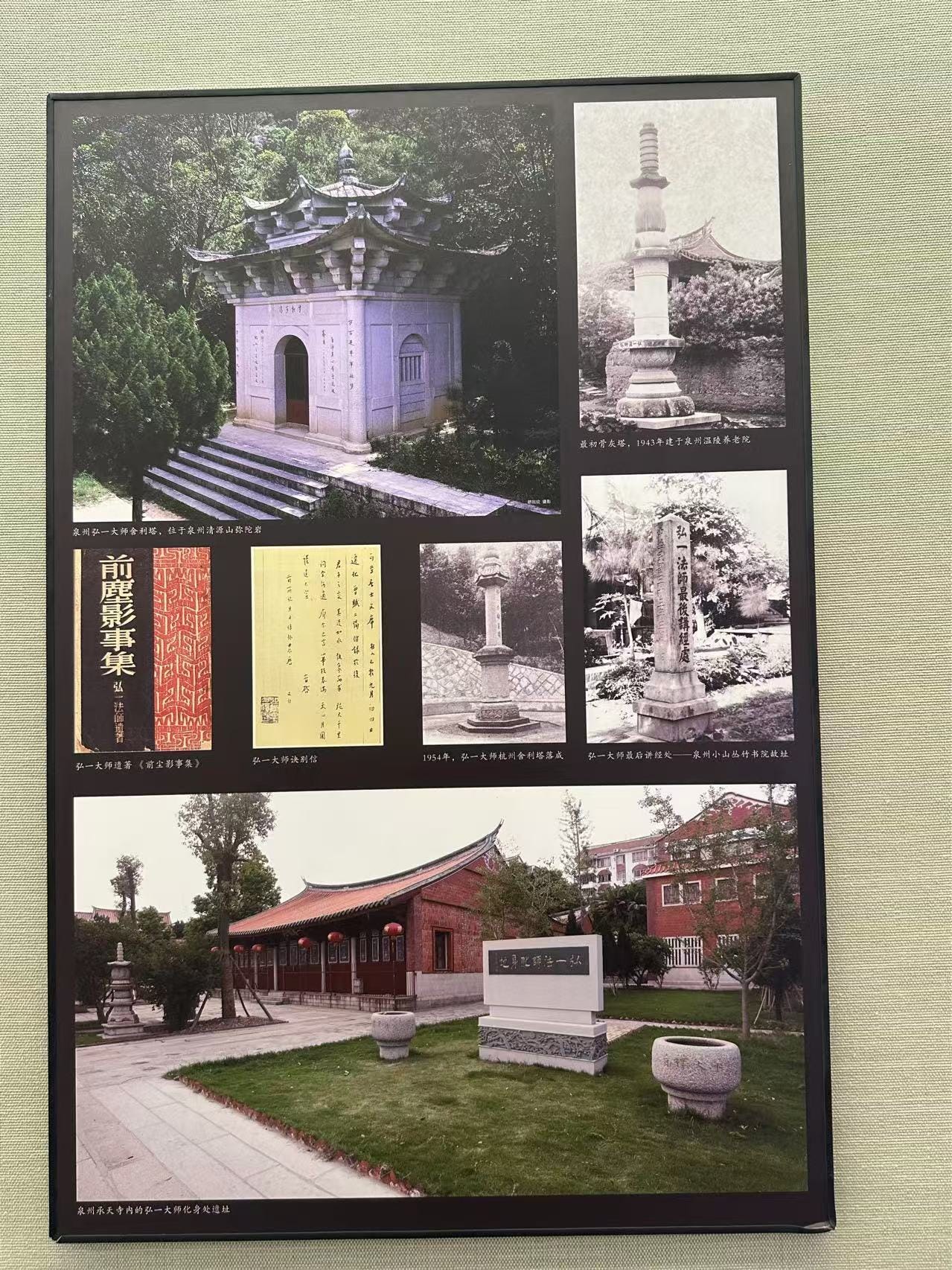

After Master HongYi was cremated, 1800 relics were collected and two stupas built. One stupa was placed at Hupao Temple in Hangzhou, and the second at Qingyuan Mountain, in Quanzhou. Qingyuan is an important Daoist mountain which we were fortunate to see the following day. That HongYi means so much to both Buddhist and Daoist institutions shows his importance as a spiritual example.

For me, existence has become (trying to) accept what comes without judgment. Participating fully, with curiosity and energy, yet not being invested in one outcome. One step leads to others, in a proliferating branching of connections. The Daodejing led me to travel writing, which led to LinYutang and SuDongpo, Confucius, Zhuangzi, and now, LiShutong. Each branch continues to reach out, creating connections and revelations that I hope are as interesting to you as they are to me.

LiShutong’s life and his storytellers present a challenge. Honestly, I’m conflicted. His genius is beyond dispute, his struggles and path are well documented, and he displayed the contents of his mind profoundly and beautifully throughout his life. But can you put your mind in his place? I find I cannot. That gulf is the bewilderment of time and culture. I sense an opportunity to set aside, taking a step closer to acceptance without judgement. We will go to the places that were significant in LiShutong’s life, looking for his storytellers and maybe finding answers.

awesome! this is crazy - i have been to the hupao area of west lake. there is another daoist temple on the other side of the lake called baopu temple.

what a lovely practice in storytelling! i was transported to the gallery.

The story is amazing, yes. However, I can't sympathize with those men having one hundred wives and three hundred children....the poor wives. 😢(Master Hongyi actually got my heart when he refused to get a third wife and chose the monastery.)