The focus of our second day in Tianjin was a location that has been on my list since the Reading Date at the JinJiang Village in Quanzhou. My wife’s book of choice was a selection of Buddhist Master HongYi’s writing. When I heard his story, that he had been a famous artist from a wealthy family, from Tianjin no less, and that in midlife had rather suddenly and unexpectedly converted to Buddhism and dedicated the remainder of his life to being a devout monk, we decided right then and there that we must learn more about him.

I don’t know, I guess the human behind the history attracts me more than their story alone. There may be glimpses of Laozi and his many editors and collaborators in The Daodejing. SuDongpo bares his heart in his poetry, and LinYutang showed me how his life and who he was inspired his work. The aphorisms of Confucius only make me think more of who the man is behind them. Their facts are often lost in mystery and myth, the fog of history and its chroniclers.

But LiShutong/HongYi should be different. HongYi is a modern man, removed from us not by hundreds or thousands of years, but decades. He was a well-known and followed person for his family background and arts long before he made the shocking transition to monkhood. The man could be said to be on the way to becoming an immortal, worshipped as Confucius, Laozi, and many others are today. Leaving Kaiyuan Buddhist Monastery, the gaps in HongYi’s history shine all the brighter for the emphasis given to his accomplishments before and after joining the faith.

I don’t know what I expect to find. This man changed his life. He left things, and people, behind. Relationships were lost to him. How did it happen? Why did he do it? I know what losing a life feels like. A life you’ve grown fully into and never gave serious thought to leaving. My old life was taken from me. That I’ve found a measure of acceptance since then lessens not the pain of the moment. Maybe Tianjin will lead me to a meaning I’ve been searching for.

I gained knowledge and insight into Li’s psychology even before entering. Li loved cats so much that, while studying in Japan, he would send telegrams home simply asking, “How were the cats today?” Anyone remember telegraphs? An international telegram in the late 1800s would have easily cost over $100 in today’s currency. Remember this, family wealth, and his sensitivity, are important to the story.

The Former Residence of LiShutong, as it is known in Tianjin, is a AAA-nationally rated Tourism site. The rating, assigned from one A to five, compares locations based on importance, safety, sanitation, etc. AAA is not too low but not high either. We found the home highly maintained and professional, and by the way, free of charge. If you are in Tianjin, you should see this.

The 1400 square meters are laid out in the old courtyard style. There are multiple smaller buildings with peaceful pathways and trees between. Each building is numbered for guests to easily move through the chronological story of Li’s life. Previously, I wrote about the major events of his growing up, education and accomplishments, and later monastic life in the Travelogue: The Artist Who Became a Monk. To avoid repeating myself, you may wish to read that here.

We have come to understand the questions that Kaiyuan Monastery left for us. What kind of home life did LiShutong have growing up? He married twice, how did his wives and children cope with his monastic turn? What circumstances led to what must have been a difficult decision to upend his life, in effect, starting a second life?

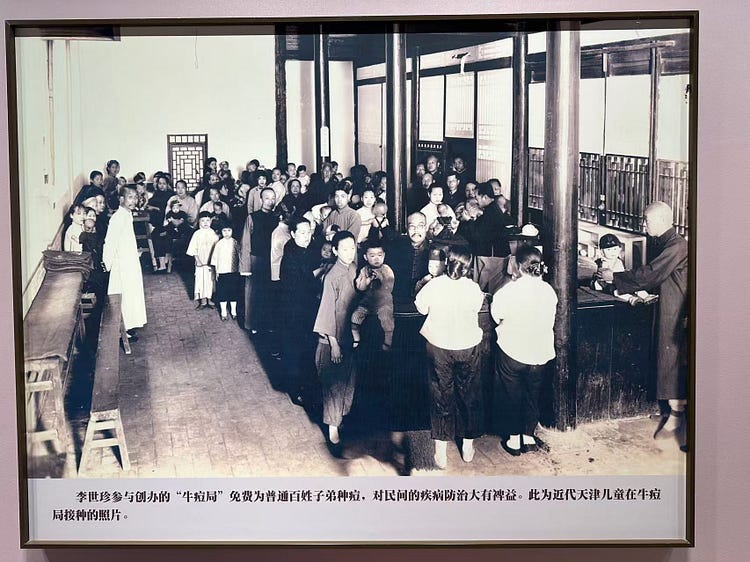

Li’s father was a banker who had control of the salt monopoly in Tianjin, because of this the family was immensely wealthy. The picture on the left is a representation of an accounting office, the far right a picture of free vaccinations for cowpox being administered to the community, an example of Li family philanthropy.

We learned that LiShtong’s father was 68 when he married Li’s mother, and she was his fourth wife. Li’s mother was 20 years old at the time and from the Shanghai area. His father passed away when he was four (pictured below). I have to suppose he never got to know him, perhaps had no memories at all. All we would know later on was that his mother was considered second class in the family due to her lower position and origin. Li is known to have been very bitter about this and resented Tianjin later.

After the death of his father, care was taken over by his mother and his two half-brothers, twelve years his senior. As befitting a son of a prestigious family, the best tutors were brought at great expense to instruct him. He was given a good foundation in the Confucian classics, calligraphy, painting, and seal carving. Years later, he wrote that he was mesmerized by the Buddhist monks who would come by the family home to perform rites and religious services.

LiShutong was married to a suitable match, a daughter from a wealthy family from the tea industry. He was 16. She is pictured and mentioned here once, as she is also shown in passing at Kaiyuan Monastery. She and LiShutong never had a warm relationship, though they had three children together. You see, it was their duty to provide heirs and the next generation.

When Li was 18 he moved to Japan to continue his education at the Tokyo School of Fine Art. His time in Japan is documented well, focusing on his accomplishments and arts while there. His output during this time was quite prolific and varied, crossing music composition, acting on the stage, nude portrait painting, and his calligraphy and seal carving. He was known as a talented and adventurous, risk-taking artist.

During his time in Japan, LiShutong apparently fell in love with a Japanese woman who became his second wife. She moved with him and stayed in Shanghai after his time in Japan while he took up a teaching position in Hangzhou. They were together for ten years and had two children together. Neither the Kaiyuan Monastery nor the Former Residence includes this information.

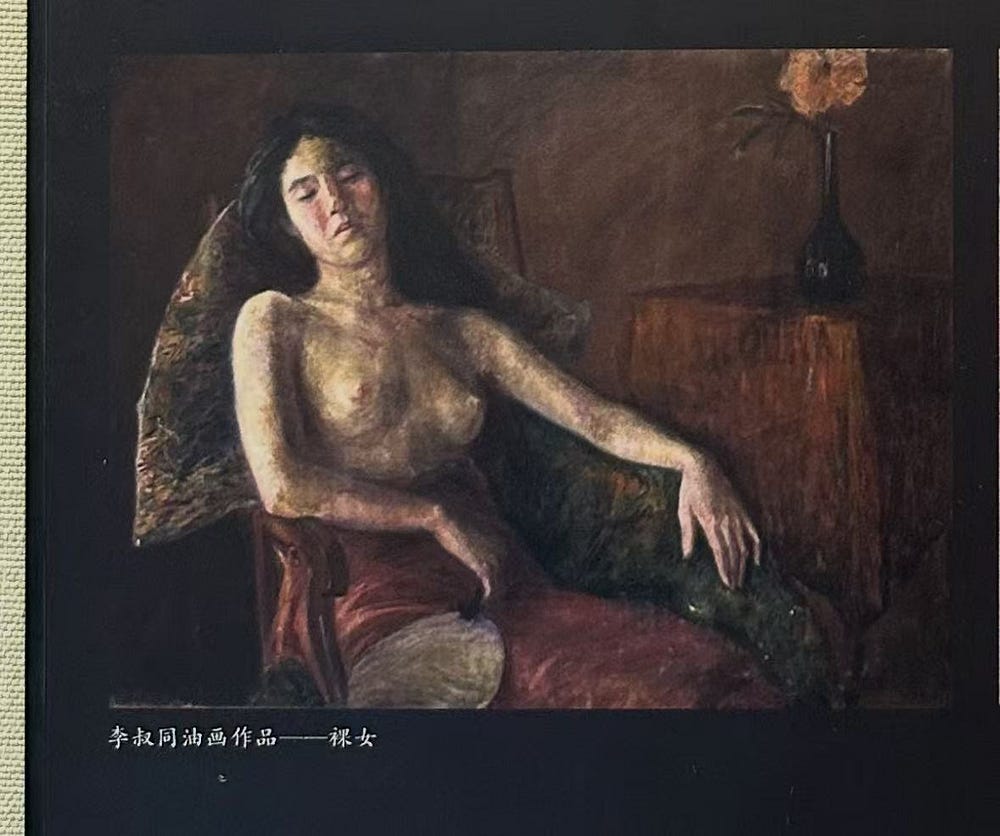

I have since the visit come to learn that this painting (below) is a nude painting by LiShutong while in Japan. His wife was the model. The picture was in the Kaiyuan collection. The description below reads, “LiShutong’s oil painting — nude”

As we walked from one space to the next, I began to suspect that coming here was not going to reveal anything. Who has any incentive to pull back the curtain on a man’s innermost motivations? The monastery? His old family home?

Meanwhile, he was so talented. A rarely gifted genius who excelled and innovated in so many spaces for the time. He was a very good stage actor, a composer, and all the other endeavours.

His portraits are so expressive; his portrait of a girl could not fail to touch even the hardest heart. I wonder who the model was, if there was a model. what did he imagine her thinking? Perhaps this is a style of self portrait.

The Residence also takes care to convey the opulence the most wealthy families enjoyed in the late 1800s. Decorated bedrooms, sitting rooms, and separate libraries for English and Chinese leisure, shows us conditions and expectations LiShutong grew up with, and the life he gave up.

As we entered the rooms depicting LiShutong’s entry into the life of a monk, I saw it. Possibly you have long anticipated what stopped me in my tracks. A portrait of a slight elderly man with a calm, placid face looking out of the frame. LiShutong had changed into Master Hongyi. More than a change of name, there is a demonstrably different person looking back at you. Could this be the same person?

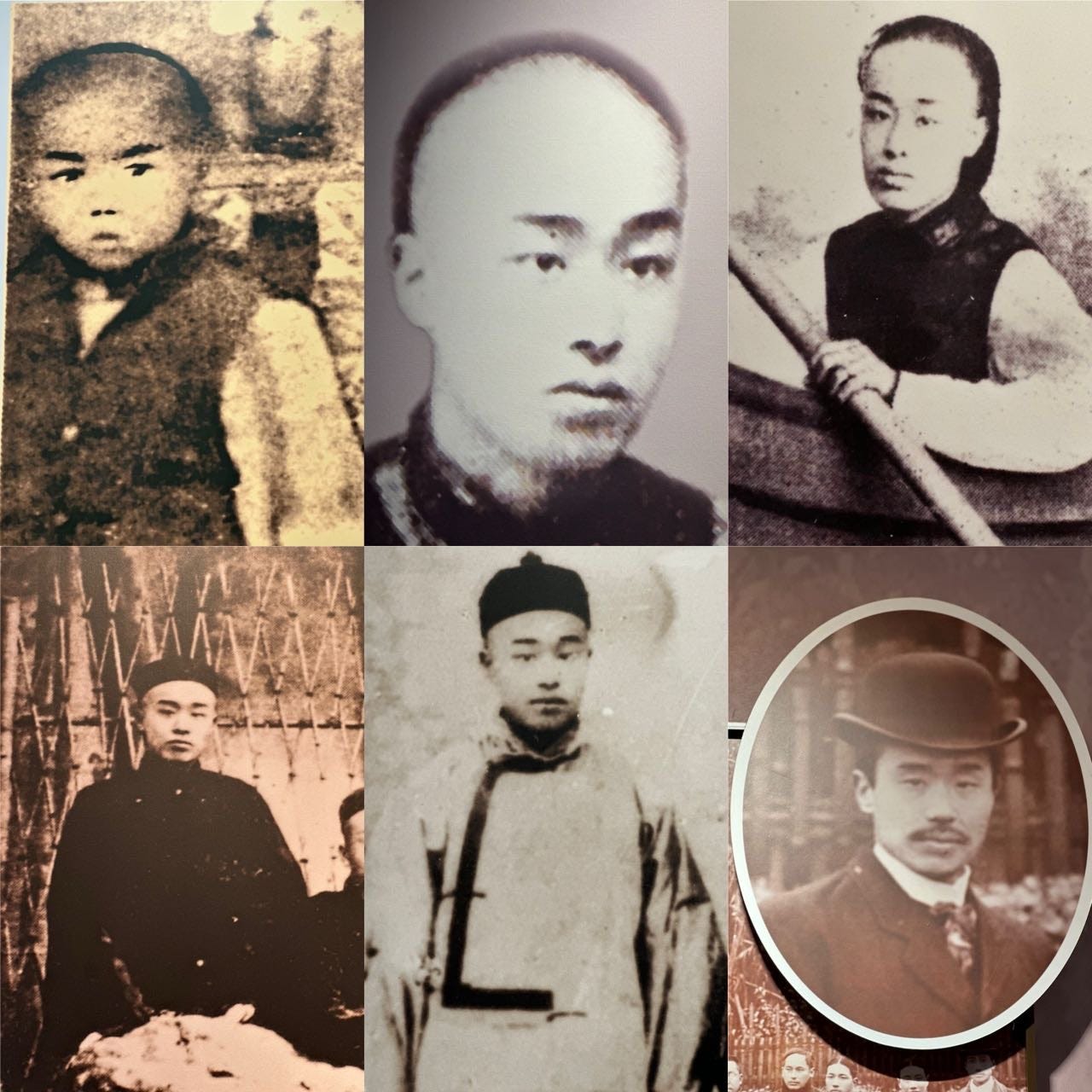

I walked back to the start of the exhibit and looked again at each of his pictures from youngest to oldest. There is something here that I believe any of us can understand.

These are the faces of a profoundly unhappy young person. The mouth angled slightly downward, the eyes and face tilted or positioned as if to avoid the camera’s gaze. A resigned look, the look of a person cornered. Reconciled to a duty, on a path he never asked for or chose. Until that fateful series of quick events that led him to say “No.”

And now see a man who is confident and proud. A serene and pleased upturn of the lips, with a penetrating gaze that looks right down the barrel of the camera. Erect posture, straight and strong even for an older man who we know was not in the best health. Even his hands, visible to the front, open and welcoming. He had found something special, something many of us search our whole existence for. Peaceful satisfaction.

Maybe no one alive now knows what happened, I surely don’t. But maybe… enough was just enough. People can only take so much before they break. Most of us break quietly, inside, known only by a few. We hide our pain behind closed doors, continuing to project a vision of perfection through our brightly lit screens. We can’t all be as well regarded as LiShutong, and break so dramatically.

Just maybe, the obligations heaped upon him by family tradition, by society’s demands, the stark fact of never making a decision for himself, could not be borne any longer. Whatever the omissions in the story, I felt his distress and do not begrudge him his relief. Existence falls harshly on all of us. We endure it in our own ways.

My search for understanding LiShutong and myself is not exhausted. We will go next to Hangzhou, to the Hupao Temple where he had his revelatory experience and was formally inducted into the monastic life. His writing and literature describing his life are on my reading list. I am grateful for his example, his test of acceptance and understanding. Most of all, I am grateful for your joining me.

Love those portraits, so cool!!

The weight of duty to a soul that is artistic, expressive, and free is the heaviest weight of all.

Reading this letter brought up thoughts of my own experiences, being caught under the weight of cultural expectations and opening up to pursue my own gifts and talents. Weaving them both or choosing one all together.

I admire the way you put his story together! I was thinking “ if he read this newsletter, it would bring him so much joy to see his life and creations honored and respected like this” he is indeed talented!! Love the tattered details in his paint work. Happy new month! 🫶🏾🌹✨