In our day, Quanzhou is a city of seven million and faces the Taiwan Strait. Despite being Fujian Provinces largest metropolitan city, I always thought of Quanzhou as Fujian’s third city, behind Fuzhou, the capital, and Xiamen, the younger, flashier brother. Only a chance reading here on Medium brought Quanzhou to mind as a destination worth a look.

Quanzhou position and power dynamics were quite different 1000 years or so ago. Then the city of 500,000 was an international powerhouse, China’s leading city for export and import. The way we thought of Shanghai or Hong Kong in the 1990s and early 2000s, Quanzhou was where foreign business people and Chinese merchants plied their trade in ceramics, sugar, perfumes, frankincense, and of course, alcohol.

The gravity of commerce pulled the arts, culture, and religious institutions to this cosmopolitan melting pot, know as Zaiton or Zayton to visitors at the time.

This is why Quanzhou has so many temple, monasteries, churches, and yes, even mosques. Buddhist, Daoist, Hindu, Muslim, and Christian communities all needed their places of worship. This density and diversity led to some interesting local customs and cross pollination of beliefs with homegrown traditions that make Quanzhou very unique. I’ve never seen any place like it.

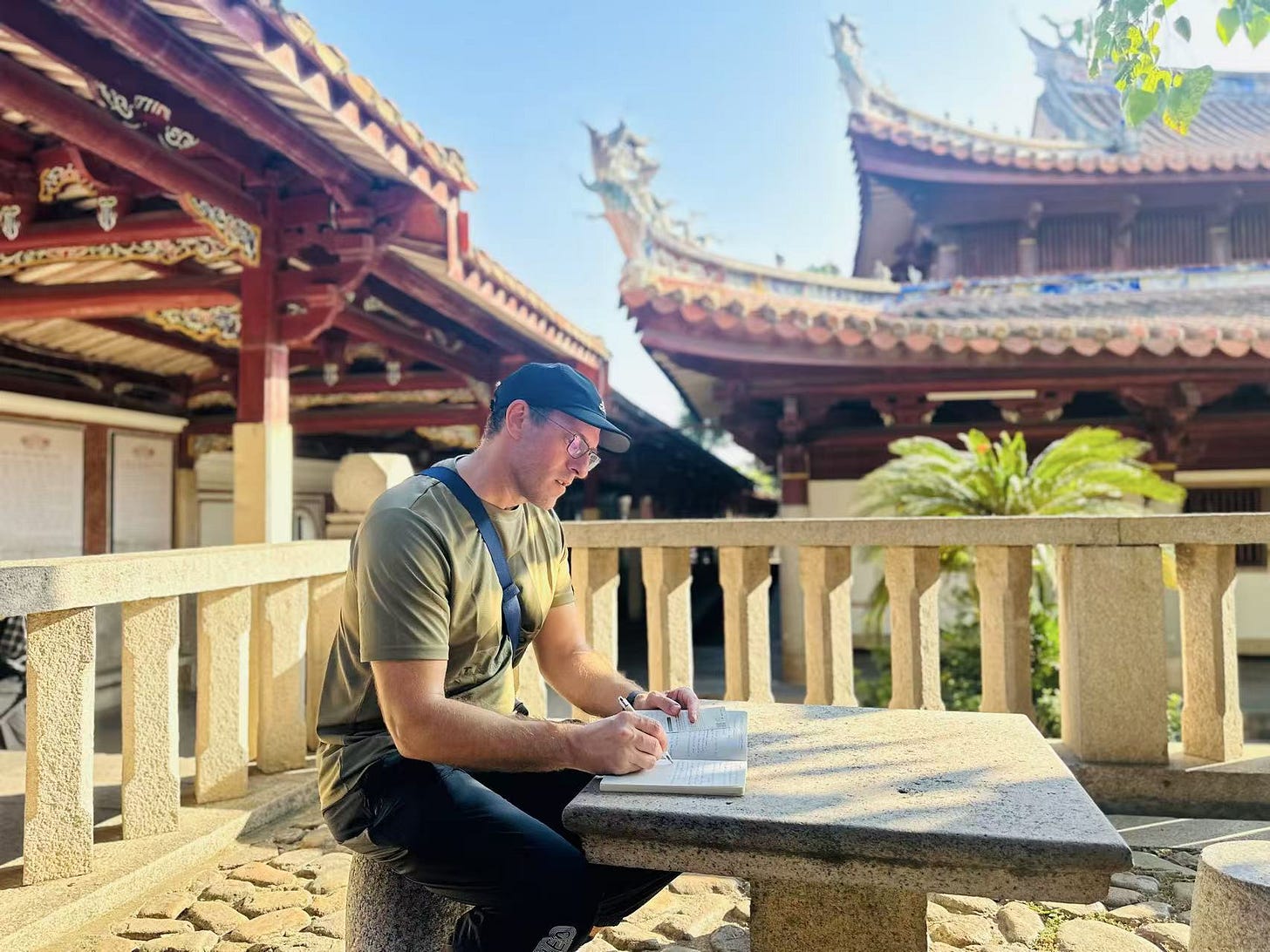

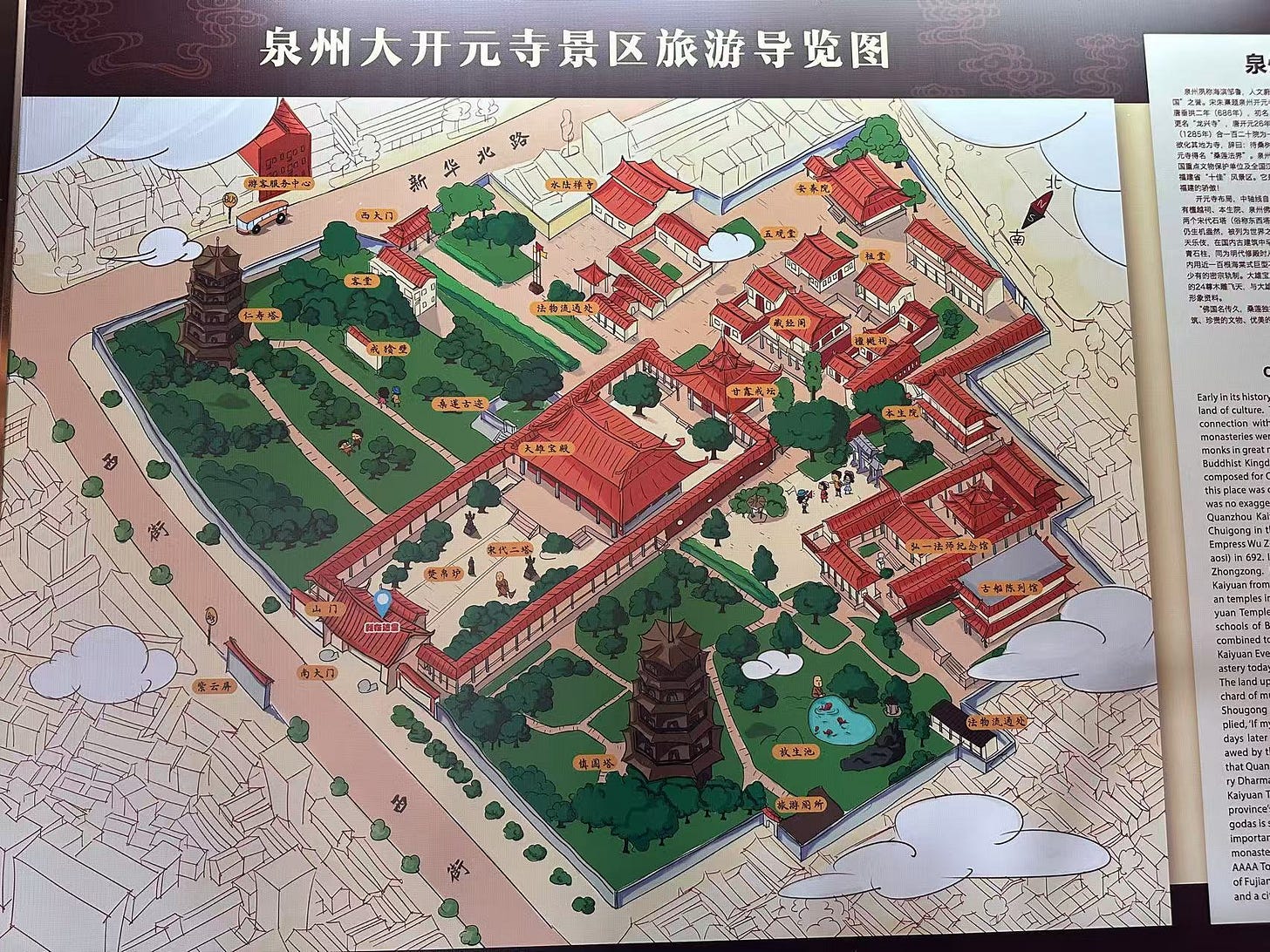

We began our trip on an afternoon lunching at XiJie. This famous street in downtown Quanzhou runs parallel to Kaiyuan (Buddhist) Monastery. The monastery is the reason XiJie existed then and the reason for it today. I can imagine the teeming crowds of all manner of social class, profession, and nationality going day and night to serve the hundreds or thousands of monks and worshippers going in and out of this giant center of worship.

As you walk along XiJie, long before you sense even the presence of the monastery, the twin stone pagodas of Kaiyuan begin to poke up above the two and three story storefronts. They watch us all, ushering us to the entrance. An entrance unguarded, open and free to all. No ticket, not even a turnstile or a bag check, simply an opening same as a public street or park. Considering the priceless nature of the treasures displayed here, this is remarkable.

Yet this is not a public park, but a fully armed and operational, though relaxed, monastery. Not relaxed like a Daoist temple, mind you, but quite relaxed compared to Chengdu’s Buddhist Daci.

Visitors have the run of the grounds, even into the administration, support, and quarters areas, though these are kept locked. So Kaiyuan is a bustling place. Everyone who visits Quanzhou has reason to visit and no excuses. There were tour groups doing the rounds in many languages. We heard groups from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and Malaysia.

The other class of visitor, predominantly local, is the costume photographers and their clients. Costume shops line both sides of XiJie. This is big business! Individuals and small groups, almost always female — but not always!- dolled up in Song dynasty fashions, being led by their photographers to the best spots. They look cute and have a fun time laughing at the results.

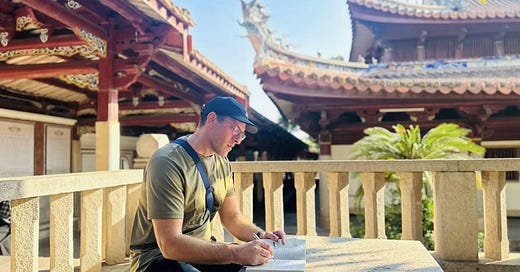

And yet it is possible to find a quiet, contemplative corner in Kaiyuan. Past the touring and the posing, you can leave almost everyone behind.

Almost everyone.

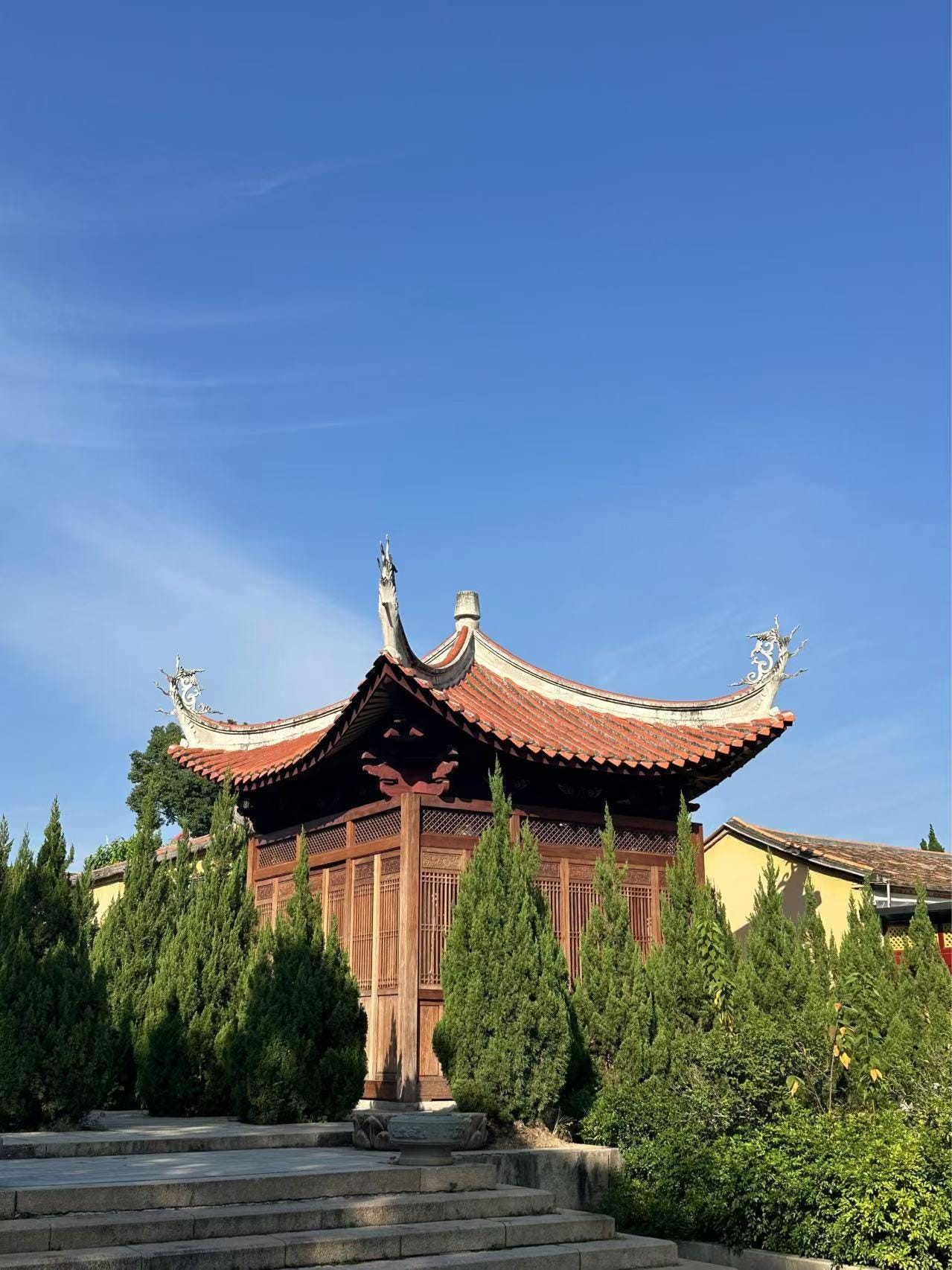

This altar doesn’t receive too many regular visitors, flanked by fir trees ranked three or four deep. A ghostly figure could be spotted walking in and out of sight among the trees. A shaven head solitary monk in grey robes was slowly walking a circuitous path among the maze of trees, repeating a mantra in a low singsong. Why he was doing this, what he was thinking, we will never know but I got the impression he was where he intended to be, doing what he wanted to do. We left him to his practice.

As we approached the alter, walking under the eaves to peer into the dark, a melodious yet authoritative voice entered consciousness, getting louder the closer we came. At first the voice seemed to be singing, then resolved into a kind of poetic chanting, and we recognized the voice of a teacher speaking to a groups of students. Might we see teaching to a group in person? But no, this wasn’t meant to be. Someone just inside the opening, hiding off to the side, was listening to a recorded lecture. We didn’t feel he would want to be disturbed.

Returning to the Main Hall, approaching from the back as we were, these two special columns were the first feature to study. These two columns are imported from a Hindu temple. I had so many questions. Apparently, Tamil merchants had built a Hindu temple during the Yuan dynasty (12–13th century), and when that temple was closed for reasons, these two columns were repurposed to preserve them as artifacts in Kaiyuan. Both columns are protected from incidental damage. The carvings include Krishna, Brahma, and other figures from Hindu mythology, of which I know very little.

Kaiyuan’s importance as a repository for artifacts and cultural relics is wide-ranging. This temple is special for having been spared destruction during the Cultural Revolution. Many places of worship were not given this protection. Because of this status, Kaiyuan became a place to collect artifacts from all over the city, particularly but not exclusively, Buddhist artifacts. These include an extensive sutra library (not open to public viewing), a gate from the Confucius temple, and an elaborately carved Qilin Wall from 1795.

A Qilin, also called a Kirin or Kylin, is a mythical creature like a unicorn, which this is sometimes called, a Chinese unicorn. The one here has the head of a dragon, the hooves of an ox, the tail of a lion, and the scales of a fish. There are different versions. I remember one of these is associated with Confucius’s birth.

This little angelic figure decorates the Main Hall. This one is holding paper, but others may hold brushes or musical instruments. The twenty-four represent the twenty-four divisions of a Chinese solar year.

This the character for chan, or zen. Learn how to write it here.

Chan Buddhism came from India, and became Zen in Japan. Looking at this symbol and the adoration and eagerness to be photographed with it, I become acutely away of my minimal knowledge of Buddhism and Daoism generally. With some intention and patience, I hope to increase my understanding of these belief systems and organizations that have such an impact on our cultures.

One thing I did learn that I found very interesting was this explanation of Chan Buddhism’s approach to meditation.

Chan Buddhism understands meditation from a Daoist point of view, that of total absorption in an activity. Any activity, including traditional meditation, but the action can be anything. Chopping wood, reading a book, washing clothes, going for a walk, it is about the losing of the self in the activity. That sounds like the lessening of consciousness that “being in the zone” brings, and I like that interpretation.

This barely scratches the surface of a monastery that is more like an open air museum of a thousand years of religious and regional history. I walked past so many things unaware of the significance, I had notes for things to look for that I couldn’t find, and this article would be three times longer and you’d be so bored and swamped with minutiae that we wouldn’t be having fun. And we’re here to have fun!

Kaiyuan stirs us to make a return visit, and we will.